KEYNOTE LECTURE AT THE INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR MONETARY AND BANKING STUDIES (ICMB),

GENEVA, 28 APRIL 2009

Main characteristics of unconventional measures

When conventional tools can no longer achieve the central bank’s objective, policy-makers are confronted with a number of issues.

- First, the unconventional tools include a broad range of measures aimed at easing financing conditions. Having this menu of possible measures at their disposal – which are not mutually exclusive ones – monetary policy-makers have to clearly define the intermediate objectives of their unconventional policies. These may range from providing additional central bank liquidity to banks to directly targeting liquidity shortages and credit spreads in certain market segments. The policy-makers then have to select measures that best suit those objectives.

- Second, they should be wary of the possible side-effects of unconventional measures and, in particular, of any impact on the financial soundness of the central bank’s balance sheet and of preventing a return to a normal market functioning.

In general, unconventional measures can be defined as those policies that directly target the cost and availability of external finance to banks, households and non-financial companies. These sources of finance can be in the form of central bank liquidity, loans, fixed-income securities or equity. Since the cost of external finance is generally at a premium over the short-term interbank rate on which monetary policy normally leverages, unconventional measures may be seen as an attempt to reduce the spreads between various forms of external finance, thereby affecting asset prices and the flow of funds in the economy. Moreover, since these measures aim to affect financing conditions, their design has to take into account the financial structure of the economy, in particular the structure of the flow of funds. Let me elaborate on the possible measures.

One way to affect the cost of credit would be to influence real long-term interest rates by impacting on market expectations. Expectations may work through several channels. For instance, the central bank can lower the real interest rate if it can induce the public to expect a higher price level in the future. If expected inflation increases, the real interest rate falls, even if the nominal interest rate remains unchanged at the lower bound. Alternatively, policy-makers can directly influence expectations about future interest rates by resorting to a conditional commitment to maintain policy rates at the lower bound for a significant period of time. Since long-term rates are prima facie averages of expected short-term rates, the expectation channel would tend to flatten the entire yield curve when policy-makers commit to stay at the lower bound. Moreover, a conditional commitment to keep the very short-term rate at the lower bound for long enough should also prevent inflation expectations from falling, which would otherwise raise real interest rates and curtail spending. In either case, if the management of expectations is successful, it would – ceteris paribus – reduce the real long term rate and hence foster borrowing and aggregate demand.

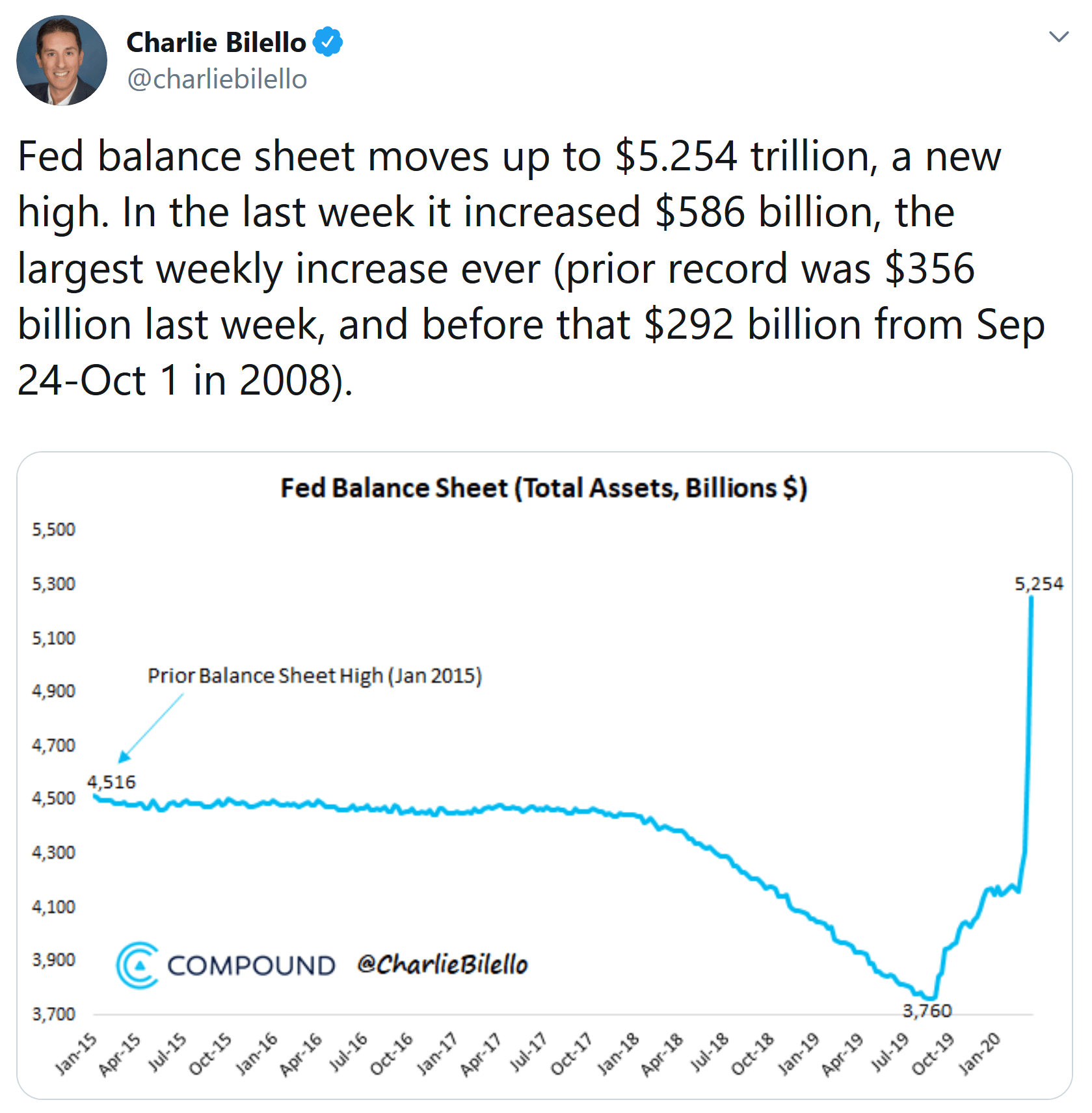

Another way in which the central bank can influence the cost of credit is by affecting market conditions of assets at various maturities – for instance, government bonds, corporate debt, commercial paper or foreign assets. Two different types of policies can be considered. The first aims at affecting the level of the longer term interest rate of financial assets across the board, independently of their risk. Such type of policy would operate mainly by affecting the market for risk free assets, typically government bonds. This policy is typically known as ‘quantitative easing’. The second policy is to affect the risk spread across assets, between those whose markets are particularly impaired and those that are more functioning. Such a policy would be usually referred as ‘credit easing’. The two types of policies affect differently the composition of the central bank’s balance sheet. Another difference is that ‘credit easing’ can generally be conducted also at above-zero levels of the short-term nominal interest rate, while quantitative easing should make sense only when the interest rate is at zero or very close to zero. However, both operations aim at increasing the size of the central bank balance sheet and therefore expanding its monetary liabilities.

Let me now consider quantitative easing and credit easing in turn.