Growth in profits have LITTLE role in determining intrinsic value.

Growth benefits investors only when the business in point can invest at incremental returns that are enticing - in other words, only when each dollar used to finance the growth creates over a dollar of long-term market value. In the case of a low-return business requiring incremental funds, growth hurts the investor."

If understood in their entirety, the above paragraph will surely make the reader a much better investor.

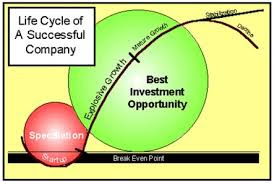

Growth in profits will have little role in determining value. It is the amount of capital used that will mostly determine value. Lower the capital used to achieve a certain level of growth, higher the intrinsic value.

There have been industries where the growth has been very good but the capital consumed has been so huge, that the net effect on value has been negative. Example - US airlines.

Hence, steer clear of sectors and companies where profits grow at fast clip but the return on capital employed are not enough to even cover the cost of capital.

It captures a fundamental, yet often misunderstood, principle of value investing. Let's break it down, discuss its implications, and summarize.

Core Thesis: Growth is Not a Free Good

The central argument is a direct challenge to conventional market thinking, which often equates "growth" with "value." The passage asserts that growth in profits is not inherently valuable. It only becomes valuable under a specific condition: when the capital required to generate that growth earns a return above the company's cost of capital.

Growth that Destroys Value: If a company (or an entire industry) must invest massive amounts of capital at low returns (e.g., 4%) to grow profits, but its cost of capital is 8%, it is destroying shareholder wealth with every new dollar invested. The profit number goes up, but the economic value per share goes down.

Growth that Creates Value: A company that can grow profits by reinvesting minimal capital at high returns (e.g., 25% on capital) is a value-creating machine. Software companies, certain branded consumer goods firms, and platforms with network effects often exemplify this.

Key Concepts Explained

"The amount of capital used will determine value."

This refers to the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). Value is a function of cash flows, and high ROIC means the business generates more cash flow per dollar of capital locked up in the business. A business with a 30% ROIC is far more valuable than one with a 10% ROIC, even with identical current profits, because its future profit growth will require less dilution or debt.

"Each dollar used to finance the growth creates over a dollar of long-term market value."

This is the value creation test. The "dollar of long-term market value" is the present value of all future cash flows that dollar of investment will generate. If that present value exceeds $1, management has created value. This is directly linked to investing at a spread above the cost of capital.

The Example of US Airlines:

This is a classic case. The industry has seen consistent growth in passenger traffic and, at times, profits. However, it is fiercely competitive, requires enormous ongoing capital expenditures (planes, maintenance, gates), and has historically earned returns below its cost of capital. The net effect over decades has been wealth destruction for equity investors, despite being a vital and growing service.

Commentary and Nuance

Echoes of Great Investors: This philosophy is pure Warren Buffett (inspired by his mentors Ben Graham and Charlie Munger) and Michael Mauboussin. Buffett famously said, "The best business is one that can employ large amounts of incremental capital at very high rates of return." He also warned about "the institutional imperative" that pushes managers to pursue growth at any cost, even value-destructive growth.

Link to "Economic Moats": A business's ability to reinvest at high rates over time is protected by its competitive advantage or "moat." Wide-moat businesses (strong brands, patents, network effects) can sustain high ROIC as they grow. No moat means competition will quickly drive returns down toward the cost of capital.

The Investor's Practical Takeaway: The passage instructs investors to look beyond the headline "profit growth" figure.

Primary Metric: Focus on Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) or ROIC.

Compare: Weigh the ROIC against the company's estimated Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC).

The Rule: Seek companies where ROIC > WACC, and where this spread is sustainable. Be deeply skeptical of high-growth companies with low or declining ROIC.

Sector Selection: As advised, be wary of sectors prone to value-destructive growth cycles—airlines, traditional telecom, capital-intensive manufacturing—unless there is a clear, structural shift toward discipline and higher returns.

Summary

In essence, the passage makes a critical distinction:

Naive View: Growth in Profits → Higher Intrinsic Value.

Sophisticated View: Growth in Profits at High Returns on Capital → Higher Intrinsic Value. Growth in Profits at Low Returns on Capital → Can Actually Destroy Intrinsic Value.

The ultimate determinant of value is not growth itself, but the quality of that growth as measured by the return on the capital required to achieve it. An investor who internalizes this shifts their focus from the top-line growth story to the economics of the business model, thereby avoiding value traps disguised as growth stories and identifying truly exceptional compounding machines. This is, indeed, what makes a "much better investor."