Know the invisible risk of keeping cash. You are robbed quietly for keeping cash in the bank. True risk is inflation.

Safer to invest in these 5 productive assets, depending on your circle of competence:

1. Businesses (stocks)

2. Productive properties

3. Yourself. Learn skills that can double your income. Cannot be taken away.

4. Controlled businesses. Business you actually operate and you control. You are the management. This is the highest risk, highest reward category. Many businesses fail. If you have the skill to execute, this maybe the best return you will ever have.

5. Precious metals and productive hard assets, e.g. productive farm, a tractor or equipment.

Here are the 4 best financial advice you will ever get:

Spend less than what you earn

Invest the difference in productive assets that you understand

Be patient.

Don't do stupid things.

Time plus rationality beats cleverness plus activity.

The person who buys great businesses at fair prices and holds them for 40 years will beat the person who trades frequently, chases trends, and pays fees to active managers. Not sometimes, ALWAYS.

Crashes are opportunities. The people who win are those who stay calm and buy. The people who lose are those who panic and sell. Temperament is more important than intelligence.

If you are young, with decades until retirement, you should be heavily invested into these productive assets.

Even in retirement, you still need growth and stability, as you may live another 30 years or more. Often, those in retirement still keep too much in cash, losing 3% to 4% in purchasing power per year..

The right amount of cash should be 6 months of expenses, your emergency funds. All else should be in productive assets mentioned above, not speculative assets.

Fear causes many to be holding too much cash. You are not in productive assets. Automate your savings into your investments through setting up systems. This takes emotion out of your investing.

Everyday inflation erodes value. Everyday you are missing compounding returns. Everyday is a day you cannot get back.

Compounding works when you give it the time to work. They kept their money in cash. They played it "safe". They avoided volatility. This guaranteed poverty. They retired poor.

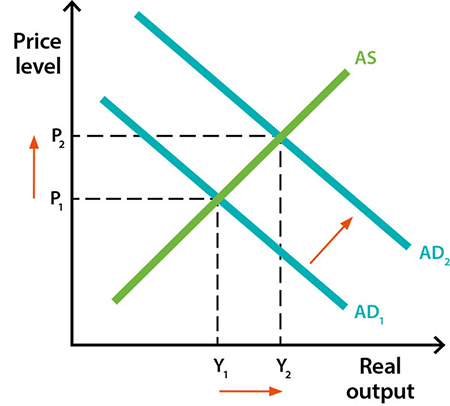

Opportunity cost. Every dollar in cash earning 1% is an opportunity cost of not earning 8% to 10% in productive assets. That difference compounds over decades represents massive foregone wealth. This is the difference between poverty and comfort. People still make the same mistake because fear is more powerful than mathematics. This is what Charlie Munger means by avoiding stupid mistakes.

TAKE ACTION TODAY

- Today, add up your cash and cash equivalents.

- Calculate your monthly expenses and multiply by 6. That is your emergency fund target.

- Whatever that is left is excess cash and should be invested.

- If you do not have an investment account, open one today, a broker's account.

- Use the excess cash into productive assets that you understand. Buy wonderful businesses at fair prices. If you don't, buy a low cost S&P index fund. Don't overthink. Don't wait for the perfect time.

- Set up automatic monthly investment payment from your paycheck. Make it systematically. This removes emotion from your investing process.

That's it. Do all these today. Doing so, you would have taken control of your financial future that most people never do.

Some of you won't do it. You will wait for the right time. You keep accumulating cash because you feel safe. Then in 30 years, you wish you have done it today. This is the tragedy. Results come from action, not knowledge without action.

Rationality versus emotion, long term thinking versus short term comfort, mathematics versus feeling.

Treating cash as your primary asset is a mistake, a predictable expensive mistake that compounds negatively over time. The above 5 productive assets categories aren't magic but rational responses to a world where inflation exists and productivity compounds.

By being consistently rational over long period of time, safety means preserving and growing purchasing power. The wealthy keeps their money in productive assets that compounds over time, never in cash. They think in decades ,not days.

Will you act now, and today? Financial security is within reach for anyone who is willing to be patient.

STOP READING AND START DOING TODAY..

Based on the transcripts provided, here is a summary of the key arguments and recommendations.

Core Problem: The Illusion of Safe Cash

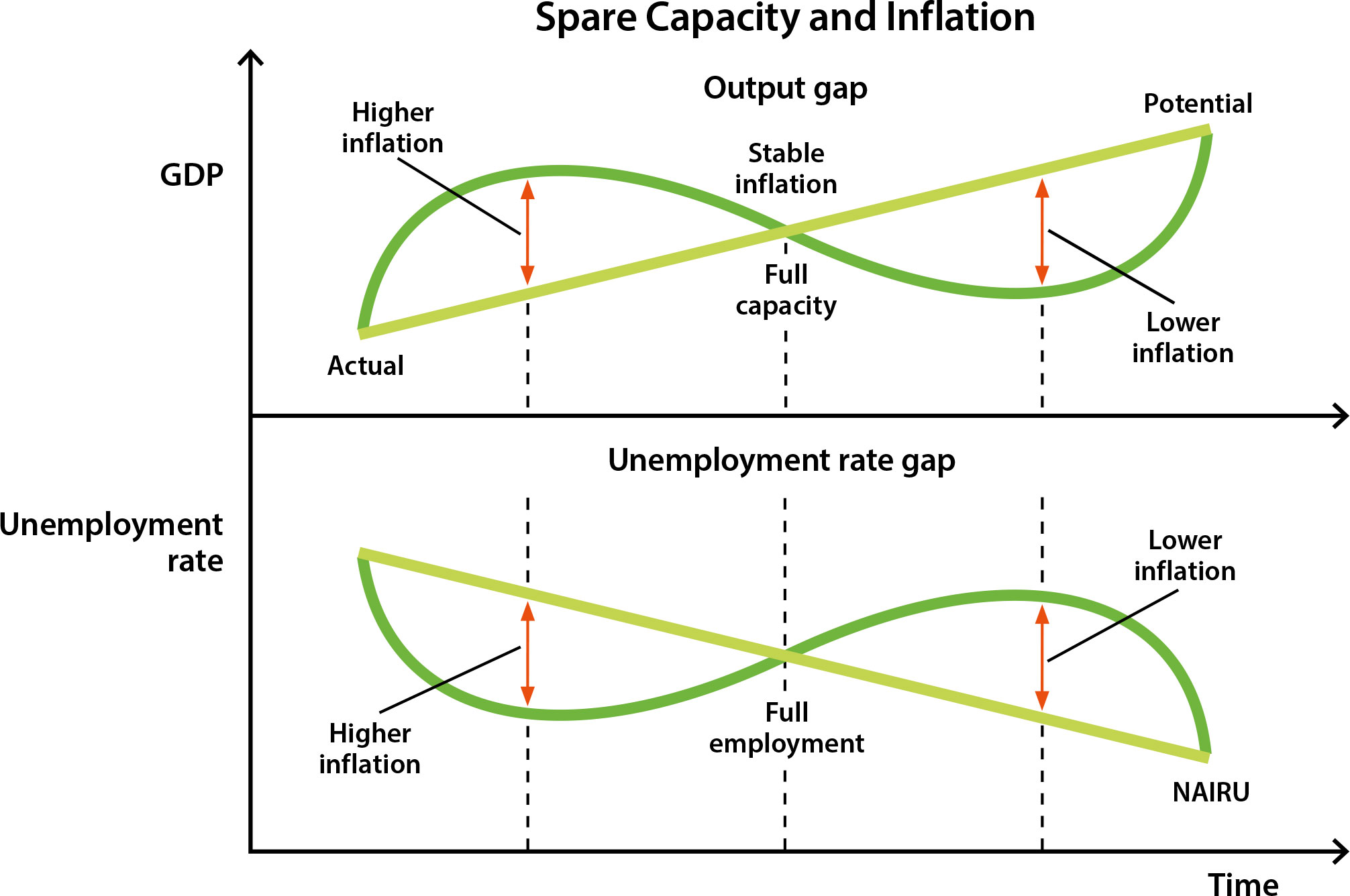

The central argument is that keeping most of your money in a bank account is not safe; it's a guaranteed loss of purchasing power due to inflation.

The Simple Math: If inflation is 3% and your savings account pays 0.5%, you are losing 2.5% of your purchasing power every year. Over a decade, this can result in a loss of about 25% of what your money can actually buy.

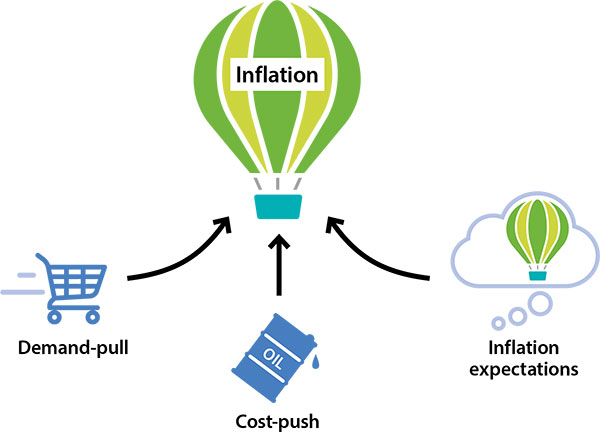

Misplaced Fear: People fear the visible volatility of the stock market (a 20% drop that might recover) more than the invisible, steady erosion of inflation (a guaranteed 30% loss over a decade). This is driven by psychological biases like "deprival super reaction tendency" (hating to lose what we have).

Key Mental Models:

Invert: Instead of asking "What should I buy?", ask "What are the ways I'm certain to lose?". The answer is that cash guarantees a loss.

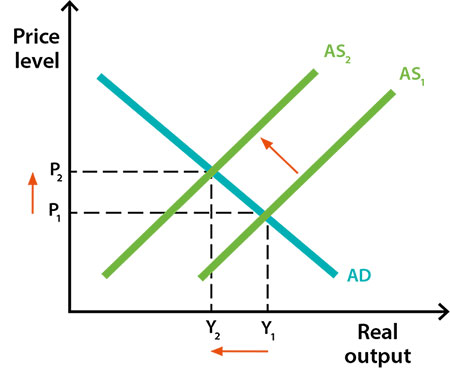

Entropy: Like disorder in physics, cash's purchasing power naturally decays unless you add energy (by investing it).

Reverse Compound Interest: Inflation compounds against you, slowly but devastatingly destroying wealth over time.

The Solution: Five "Safer" Assets That Preserve Purchasing Power

The author recommends moving away from passive cash and into active, productive assets. "Safer" here means safer in terms of preserving and growing your real purchasing power over the long term.

Productive Businesses (Stocks): Owning pieces of companies, not just trading ticker symbols.

Why: A good business has "pricing power"—it can raise prices with inflation, so its earnings and value grow, protecting you.

Crucial Caveat: This only works within your "circle of competence." You must understand the business and be able to avoid panicking during downturns.

Productive Real Estate: Property that generates income (e.g., rental properties).

Why: Rents tend to rise with inflation, while mortgage payments stay fixed, and the underlying asset often appreciates.

Test: If you wouldn't want to own the property for its income alone, you're speculating, not investing.

Yourself (Skills & Earning Power): This is the most underinvested asset.

Why: Investing in education or skills that increase your value in the marketplace can multiply your future earnings, creating more value than any other investment. This asset can't be taken away by a market crash.

Controlled Businesses (The Ultimate Asset): This is the cornerstone of the Berkshire Hathaway model.

Why: When you control a business, you have direct power over its capital allocation, strategy, and pricing. You can reinvest its earnings intelligently and fully benefit from its pricing power without relying on the judgment of others. The example of See's Candies is given—Berkshire could raise prices to directly combat inflation, something cash can never do.

This is the goal: The narrative makes it clear that building a portfolio of controlled, productive businesses is the highest-return, most rational strategy for preserving and growing wealth.

Useful Hard Assets: Assets that are functionally valuable, not just speculative.

Examples: Productive farmland, machinery that generates income.

What it's NOT: This is not speculation in gold or cryptocurrencies, which produce nothing and rely on someone else paying more later.

A Practical Framework and Final Advice

Emergency Fund: Keep 3-6 months of expenses in cash for emergencies, not years of income. Anything beyond that is losing value.

Overcoming Psychology: Understand that "social proof" (everyone does it) and "availability bias" (fearing vivid market crashes) lead to bad financial decisions.

Key Questions to Ask Yourself:

What is my circle of competence?

What is my true risk (permanent loss of purchasing power vs. temporary volatility)?

What is my time horizon?

What are the second-order consequences of holding cash?

What does inversion tell me about the guaranteed outcome of my current strategy?

The Ultimate Lesson: The path to building wealth isn't about being a genius or finding a secret. It's about being rational, patient, and disciplined; avoiding stupid mistakes; and letting compound interest work for you in productive assets instead of against you in cash.

Additional notes:

High-Quality Bonds (in specific situations): Not all bonds, and not as a primary strategy.

Why: Short-term, high-quality bonds can provide "optionality"—a slightly better return than cash while keeping powder dry for future opportunities.

Warning: If the bond's yield doesn't significantly outpace inflation, it's just a slower way to lose purchasing power, with less flexibility than cash.