Option Pricing for Beginners

I’ve had

two posts so far on the terms under which Treasury sold back to Old National the warrants on Old National stock that Treasury got in exchange for its TARP investment, so I thought it was time for an

introduction to warrant/option pricing.

The warrants received by Treasury give Treasury the right to buy common stock in the issuing bank under predefined terms. Buying the stock is called

exercising the warrant. The warrant specifies how many shares Treasury can buy; the price that it must pay to buy them (the exercise price); and the term of the warrant, meaning how long Treasury has to decide whether or not it wants to exercise the warrant. If Treasury never exercises the warrant, then it expires and nothing happens. For our purposes, a warrant is the same as a call option; there are some differences I will ignore, which are outlined

here.

Warrant terms

These warrants were part of the

terms of the TARP Capital Purchase Program, which is what Treasury used to recapitalize banks last fall, starting in October. The warrants have value for Treasury – how much, I’ll get into later. Therefore, they make it possible for Treasury to be more generous with other terms of the transaction. Arguably, the warrants helped compensate for the fact that Treasury was buying preferred stock with a very low dividend yield – only 5%. There is no way that most banks would have been able to issue new preferred stock with only 5% dividends back in October-November. Probably the more important reason the warrants were mixed in was that they made it easier to justify the transaction politically;

through the warrants, the taxpayer could “participate in the upside” if things went well, because if the stock price went up, the warrants would become more valuable.

As part of the Capital Purchase Program, banks had to give Treasury warrants on common stock equal in value to 15% of the amount of money invested. Treasury invested $100 million in Old National, so it needed warrants on $15 million worth of common stock. So it got warrants to buy 813,008 shares at an exercise price of $18.45; 813,008 * 18.45 = 15 million, or something very close to it. $18.45 represented the value of the common shares at the time of the investment. The idea is that the warrants were supposed to be “at the money;” if the stock went up, Treasury could exercise the warrants and make money; but if it went down, Treasury would get nothing (at least not from exercising the warrants).

Actually, that isn’t quite accurate, for two reasons. First, according to the original

term sheet, the exercise price was set not at the share price on the investment date itself, but as the average of the closing price for the twenty previous trading days; the idea here, which is common, is to protect both sides against day-to-day swings in stock prices. In Old National’s case, that would have been $16.35. However, in early April the

Wall Street Journal reported that Treasury changed the terms to base the exercise price on the date that the bank’s application to participate in the CPP was approved, which was an earlier date. Because November-December was a period of falling bank stock prices, in the large majority of cases the change in dating had the effect of increasing the exercise price of the warrants, thereby reducing the value of the warrants to Treasury (because it would have to pay more for each share). In Old National’s case, it produced an exercise price of $18.45 instead of $16.35.

(Ilya Podolyako actually drafted a post about this at the time, but I chose not to publish it because I didn’t want to be hammering Treasury for every little thing they did that helped the banks. But I think it’s an important part of this story. Ilya also pointed out that when private companies do this kind of thing – setting the exercise price based on market prices in the past – it’s called backdating, and it’s illegal. My apologies to Ilya for not publishing the post then.)

Those warrants have a term of 10 years, meaning that Treasury has until 2018 to decide whether or not to exercise them. They also have an unusual “Reduction” feature, which says that if the bank raises more money than Treasury invested by the end of 2009, through sales of new common or perpetual preferred stock, half of the warrants will instantly evaporate.

Warrant pricing

So how much are these things worth? On the date of the sale, Old National’s common shares were trading at $14.70 – $3.75 below the exercise price of the warrants. So if Treasury had done the crazy thing and exercised the warrants, it would have paid $18.45 for a share of stock worth $14.70, for a total loss of about $3 million.

However, the warrants themselves, like all options, always have some positive value, as long the term has not expired. You never have to exercise the warrants, so in no scenario will you be forced to lose money on them; and there is always some chance that the stock price will go above the exercise price, at which point you could exercise them and make money. The question is how much.

Conceptually speaking, you are trying to figure out the chances that the stock will someday be worth more than $18.45, times the profit you will make from exercising the warrants at that point. This clearly depends on the following parameters:

- Exercise price: The higher the exercise price, the less likely your warrant is to make you money.

- Current stock price: The higher the current price, the more likely you are to make money.

- Time to maturity: The more time you have, the higher the chances that the stock price will climb above the exercise price.

And it depends on one more parameter: volatility or, roughly speaking, the tendency of the stock price to move up and down. In the case of Old National, the stock price has to go up by $3.75 (25.5%) before the warrant can be exercised at a profit; the more volatile the stock, the more likely this is.

Making some additional assumptions, like zero transaction costs and zero dividends, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes worked out a formula to calculate the value of an option from these parameters (and the risk-free interest rate, since you are looking at the future and money loses value over time), which is now known as the Black-Scholes formula, and has been described as the central pillar, for better or worse, of modern finance. (Nassim Taleb strongly disagrees.) I think I had to derive the formula in a micro class a long time ago, but my memory of that year is a bit fuzzy, perhaps because I met my wife in that class.

In any case, the formula incorporates this useful intuition: To calculate the value of an option, you only need to know the expected value of exercise on the maturity date. This is because, theoretically, that is the only day on which you should ever exercise an option. Even if your option is $10 “in the money” (market price exceeds exercise price by $10), there is always a little bit of extra option value, because the potential upside is infinite, and the potential downside is bounded by $10.

Note that the formula says you can price an option without even having an opinion about the fundamental value of the underlying stock – all you need are its current price and its volatility. This is consistent with a general (though not necessarily correct) principle that stock markets always efficiently price assets, so any opinion you may have about the stock’s fundamental value is foolish.

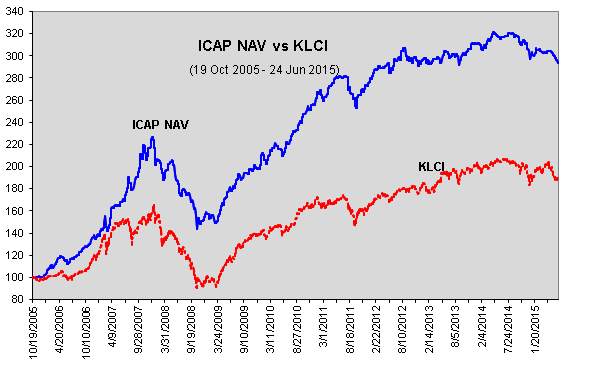

Also note that the key assumption in the formula is that stock prices will move randomly with constant volatility, and the key parameter in the formula is volatility. The other inputs are basically observable (though not quite in the case of the risk-free rate), but volatility is not. You need to know the volatility of the stock price between now and the maturity date, but all you can see is its volatility in the past. This makes option pricing especially difficult right now, because stock price volatility has been much higher over the last eight months than over the previous eight years. (The chart is the implied volatility of the S&P 500 since 2000.)

So if you use the volatility over the last eight months, you will get a much higher warrant value than if you use the volatility over the last eight years. More fundamentally, using any volatility assumption based on past data falls into the trap of assuming that the future will be like the past. This is never a foolproof assumption, and the longer the timeframe you are looking at, the worse the assumption becomes. It usually may not matter a lot for typical short-dated options (30 days, 60 days, etc.) – unless the world changes during those 30 days – but it matters a lot for long-dated warrants, like the 10-year warrants that Treasury got.

Real stocks also pay dividends, and the higher the future dividends, the less your warrant will be worth – because those dividends essentially come out of the future stock price. So your formula has to have some estimate of what dividend payouts will be. Again, this is especially hard right now, because many banks – including Old National – have drastically cut their dividends recently, and it’s difficult to predict when they will go back to paying higher dividends.

Finally, the “Reduction” feature of the TARP warrants throws another wrench into the works. To value the warrants, you have to take into account the fact that half of them could vanish if Old National raises $100 million by issuing stock before the end of the year; and as long as the warrants were outstanding, they had an incentive to raise that money. That involves making guesses about the overall funding climate, and the corporate strategy of Old National, neither of which can be statistically estimated.

So now you should know enough to understand the three key assumptions behind the estimates in

Linus Wilson’s paper. (However, the Bloomberg story does not provide its option pricing assumptions.) You should also be able to follow the discussion over assumptions between q and Sandrew in the comments to my previous post,

beginning here.

What should Treasury have done?

q, a regular commenter here, concludes that the price Treasury got is within the range of reasonableness, given his preferred set of assumptions. However, he

also says (agreeing with

Nemo) that Treasury should not have negotiated a sale to Old National, but should have simply held onto them until maturity (remember, you don’t want to exercise them early); if the real issue was restrictions placed on TARP money, the government could have rolled them back (for banks that bought back their preferred shares). Or, if Treasury didn’t want to hold onto them, they could have auctioned them off.

While these are economically superior to simply negotiating a sale in a market with a single potential buyer (Old National), it gets us into the complicated world of TARP terms and conditions. First, the original term sheet said that Treasury could not sell more than 50% of the warrants before the end of 2009, because, remember, 50% of the warrants would vanish if the bank made a qualifying equity offering. Still, Treasury could have sold half and then held the rest; this would have had the salutary effect of giving Old National an incentive to raise new capital.

Second, assuming Treasury did not sell the warrants, when Old National bought back its preferred shares, it got the right to buy back the warrants at “fair market value” – but there is no market. (You can get a quote on short-dated options, but not long-dated ones – these are typically over-the-counter.) I haven’t found the implementation rules, but an article in

Fortune said this:

February’s stimulus legislation – which gave TARP recipients the right to repay funds without raising new capital or observing any waiting period – specified that Treasury must liquidate a bank’s warrants at the current market price after it repays its TARP preferred stock.

I gather from bits and pieces I remember reading that there is some sort of appraisal process where the bank and Treasury first try to agree on a value, and I believe if that fails then there is supposed to be an auction. Auction participants would know all about option pricing, of course, and would apply a range of assumptions; presumably the sale would go to the buyer with the highest volatility assumption, which would probably (but not certainly) yield a higher price than Treasury got.

Of course, the banks have their opinion about all this (from the same Fortune article):

The American Bankers Association trade group last week sent Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner a letter calling for the government to eliminate the warrant-repayment provision altogether. The ABA said repurchasing the warrants amounts to an “onerous exit fee” for banks that have already repaid in full the funds they got from Treasury. . . .

Treasury must attempt to liquidate the warrant, the stimulus legislation says. But the ABA decries this as well, saying in its letter that selling the warrant to a third party could unfairly dilute a bank’s shareholders.

In other words, Treasury should just rip up the warrants – even though the warrants were one reason why the banks got investments on such generous terms in the first place. How times have changed since last fall.

By James Kwak

http://baselinescenario.com/2009/05/22/option-pricing-for-beginners/