Keep INVESTING Simple and Safe (KISS)***** Investment Philosophy, Strategy and various Valuation Methods***** Warren Buffett: Rule No. 1 - Never lose money. Rule No. 2 - Never forget Rule No. 1.

Tuesday, 25 June 2024

Friday, 14 June 2024

Supply Shocks and Stagflation

Box: Supply Shocks and Stagflation

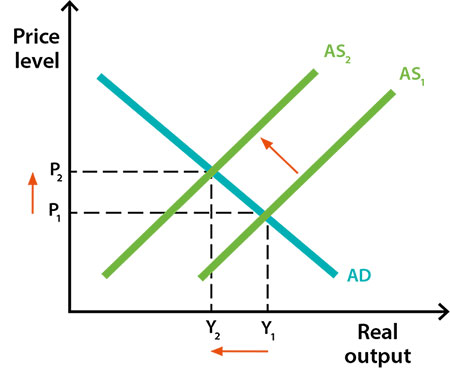

If a supply shock is sufficiently large or persistent, it not only causes cost‑push inflation, but can noticeably reduce both the current and potential level of output in an economy. In this case, there can be the unusual combination of a period of ‘stagnation’ as output declines at the same time that prices are rising. This combination of stagnant growth – with high or rising unemployment – and high inflation is referred to as stagflation. Stagflation can become entrenched when inflation expectations are not well anchored.

The 1970s were a period of stagflation that featured two oil price shocks. In October 1973, the members of OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), as well as Egypt and Syria, imposed an oil embargo on industrial nations that had supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War of the same period. The embargo resulted in a quadrupling of oil prices and energy rationing, culminating in a global recession in which unemployment and inflation surged simultaneously. Central banks did not target inflation at this time, and this was the start of a prolonged period of high inflation in many economies.

Inflation expectations

Inflation expectations

Inflation expectations are the beliefs that households and firms have about future price increases. They are important because expectations about future price increases can affect current economic decisions that can influence actual inflation outcomes. For example, if firms expect future inflation to be higher and act on those beliefs, they may raise the prices of their goods and services at a faster rate. Similarly, if workers expect future inflation to be higher, they may demand higher wages to make up for the expected loss of their purchasing power. These behaviours, sometimes called ‘inflation psychology’, can contribute to a higher rate of actual inflation so that expectations about inflation become self-fulfilling.

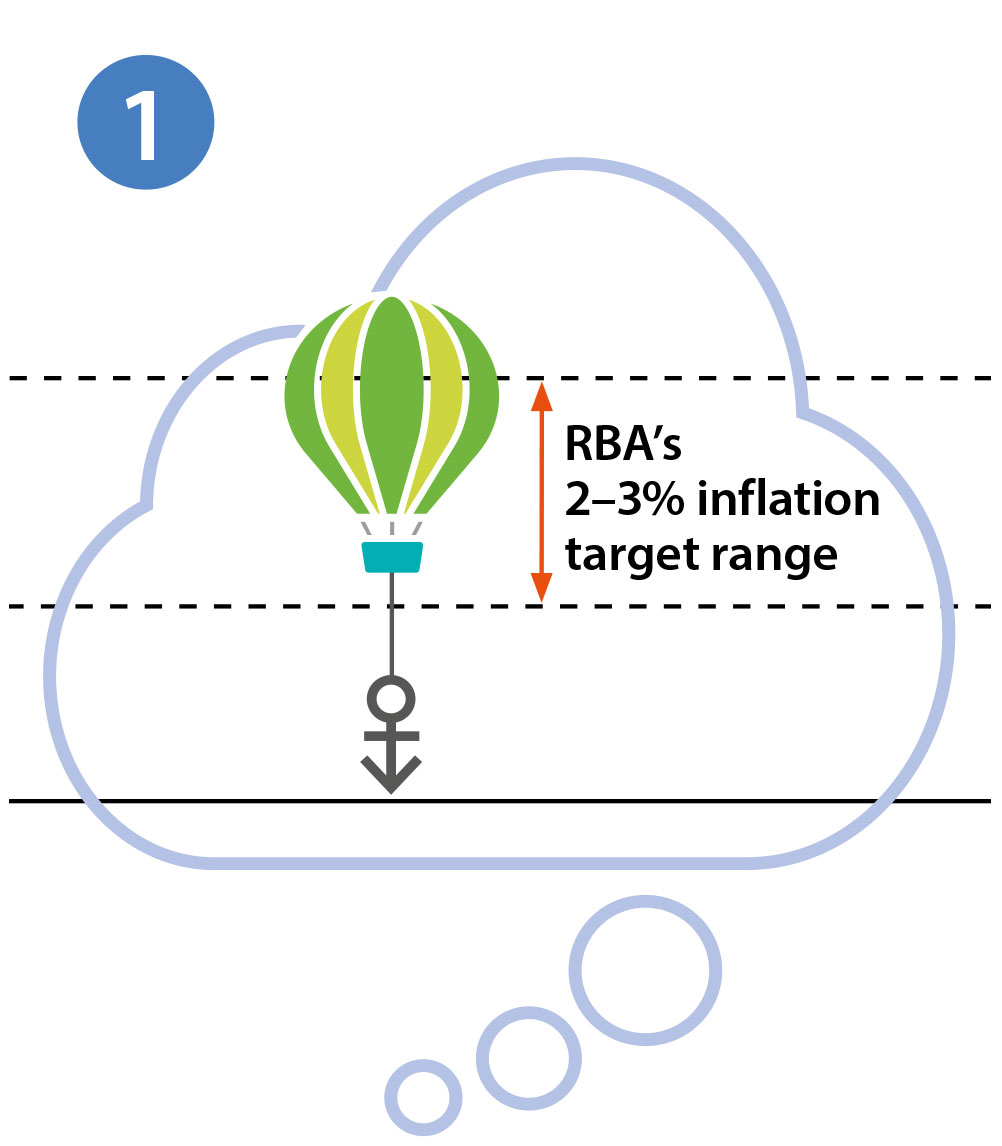

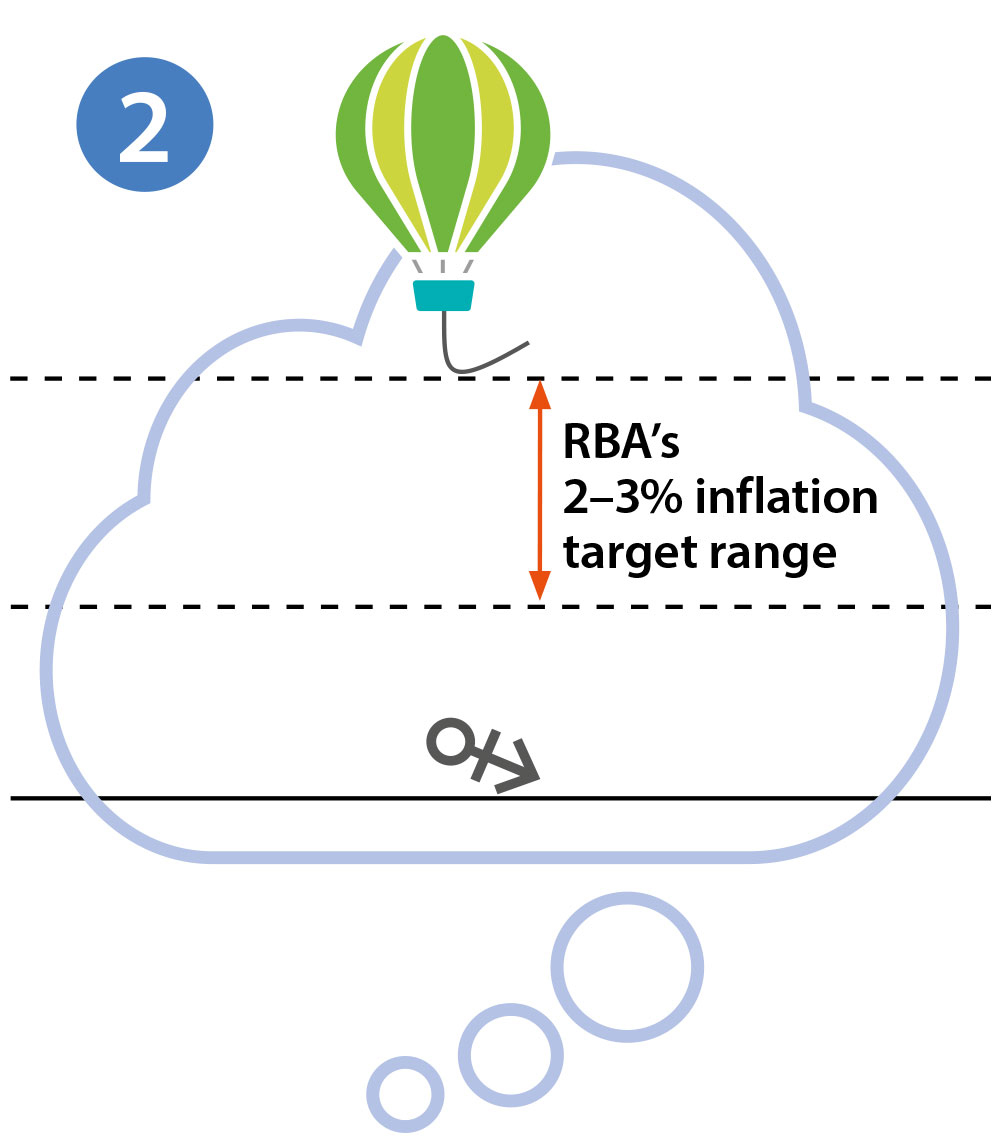

Given that inflation expectations can influence actual price and wage setting, the extent to which inflation expectations are ‘anchored’ has implications for future inflation outcomes. For example, if households' and firms' expect that inflation will return to the central bank's inflation target at some point in the future, regardless of what current inflation is, we describe their expectations as being ‘anchored’ to the inflation target. When expectations are anchored, a period of higher inflation – perhaps resulting from a cost‑push event – will not cause households and firms to change their behaviour and, as a result, inflation is likely to eventually return to its target. But if the inflation psychology of households and firms shifts and inflation expectations move away from the central bank's inflation target (i.e. they become ‘unanchored’), a period of higher inflation will become persistent because households and firms will expect inflation to be higher in the future and adjust their behaviour accordingly. Consequently, it is much easier for a central bank to manage inflation if inflation expectations are anchored rather than unanchored.

Illustrative Example of Anchored and

Unanchored Inflation Expectations

While inflation expectations have an important influence on actual inflation outcomes, they are not directly observable. Instead, policymakers such as the Reserve Bank have to rely on measures of expected inflation that are based on surveys (where people are asked their views about the inflation outlook directly) or financial assets like government bonds (where the price of the asset reflects assumptions made about the future path of inflation, see Explainer: Bonds and the Yield Curve).

Cost-push inflation

Cost-push inflation

Cost-push inflation occurs when the total supply of goods and services in the economy which can be produced (aggregate supply) falls. A fall in aggregate supply is often caused by an increase in the cost of production. If aggregate supply falls but aggregate demand remains unchanged, there is upward pressure on prices and inflation – that is, inflation is ‘pushed’ higher.

An increase in the price of domestic or imported inputs (such as oil or raw materials) pushes up production costs. As firms are faced with higher costs of producing each unit of output they tend to produce a lower level of output and raise the prices of their goods and services. This can have flow-on effects by pushing up the prices of other goods and services. For example, an increase in the price of oil, which is a major input in many sectors of the economy, will initially lead to higher petrol prices. However, higher petrol prices will also make it more expensive to transport goods from one location to another which, in turn, will result in increased prices for items like groceries.

Cost-push inflation can also arise due to supply disruptions in specific industries – for example, due to unusual weather or natural disasters. Periodically, there are major cyclones and floods that damage large volumes of agricultural produce and result in significant increases in the price of processed food and both takeaway and restaurant meals, resulting in temporary periods of higher inflation.

Imported inflation and the exchange rate

Exchange rate movements can also affect prices and influence inflation outcomes. A decrease in the value of the domestic currency − that is, a depreciation − will increase inflation in two ways. First, the prices of goods and services produced overseas rise relative to those produced domestically. Consequently, consumers pay more to buy the same imported products and firms that rely on imported materials in their production processes pay more to buy these inputs. The price increases of imported goods and services contribute directly to inflation through the cost-push channel.

Second, a depreciation of the currency stimulates aggregate demand. This occurs because exports become relatively cheaper for foreigners to buy, leading to an increase in demand for exports and higher aggregate demand. At the same time, domestic consumers and firms reduce their consumption of relatively more expensive imports and shift their purchases towards domestically produced goods and services, again leading to an increase in aggregate demand. This increase in aggregate demand puts pressure on domestic production capacity, and increases the scope for domestic firms to raise their prices. These price increases contribute indirectly to inflation through the demand-pull channel.

In terms of imported inflation, the exchange rate has a greater influence on inflation through its effect on the prices of goods and services that are exported and imported (known as tradable goods and services), while prices of non-tradable goods and services depend more on domestic developments.

Demand-pull inflation

Demand-pull inflation

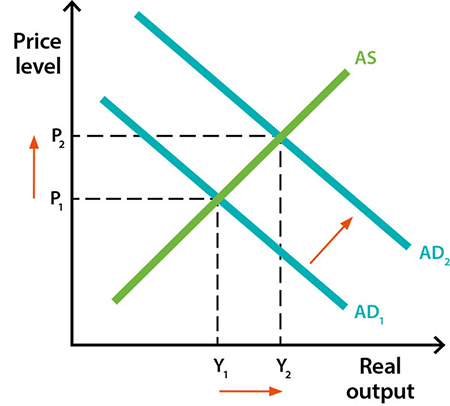

Demand-pull inflation arises when the total demand for goods and services (i.e. ‘aggregate demand’) increases to exceed the supply of goods and services (i.e. ‘aggregate supply’) that can be sustainably produced. The excess demand puts upward pressure on prices across a broad range of goods and services and ultimately leads to an increase in inflation – that is, it ‘pulls’ inflation higher.

Aggregate demand might increase because there is an increase in spending by consumers, businesses or government, or an increase in net exports. As a result, demand for goods and services will increase relative to their supply, providing scope for firms to increase prices (and their margins – which is their mark-up on costs). At the same time, firms will seek to employ more workers to meet this extra demand. With increased demand for labour, firms may have to offer higher wages to attract new staff and retain their existing employees. Firms may also increase the prices of their goods and services to cover their higher labour costs.[2] More jobs and higher wages increase household incomes and lead to a rise in consumer spending, further increasing aggregate demand and the scope for firms to increase the prices of their goods and services. When this happens across a large number of businesses and sectors, this leads to an increase in inflation.

The opposite will happen when aggregate demand decreases; firms facing lower demand will either pause hiring or make staff redundant which means that fewer staff are required. This puts upward pressure on the unemployment rate. More workers searching for jobs means that firms can offer lower wages, putting downward pressure on household incomes, consumer spending and the prices of their goods and services. As a result, inflation will decrease.

The supply of goods and services that can be sustainably produced is also known as the economy's potential output or full capacity. At this level of output, factors of production, such as labour and capital (which includes the machines and equipment firms use to produce their goods and services) are being used as intensively as possible without putting upward pressure on inflation. When aggregate demand exceeds the economy's potential output, this will put upward pressure on prices. When aggregate demand is below potential output, this will put downward pressure on prices.

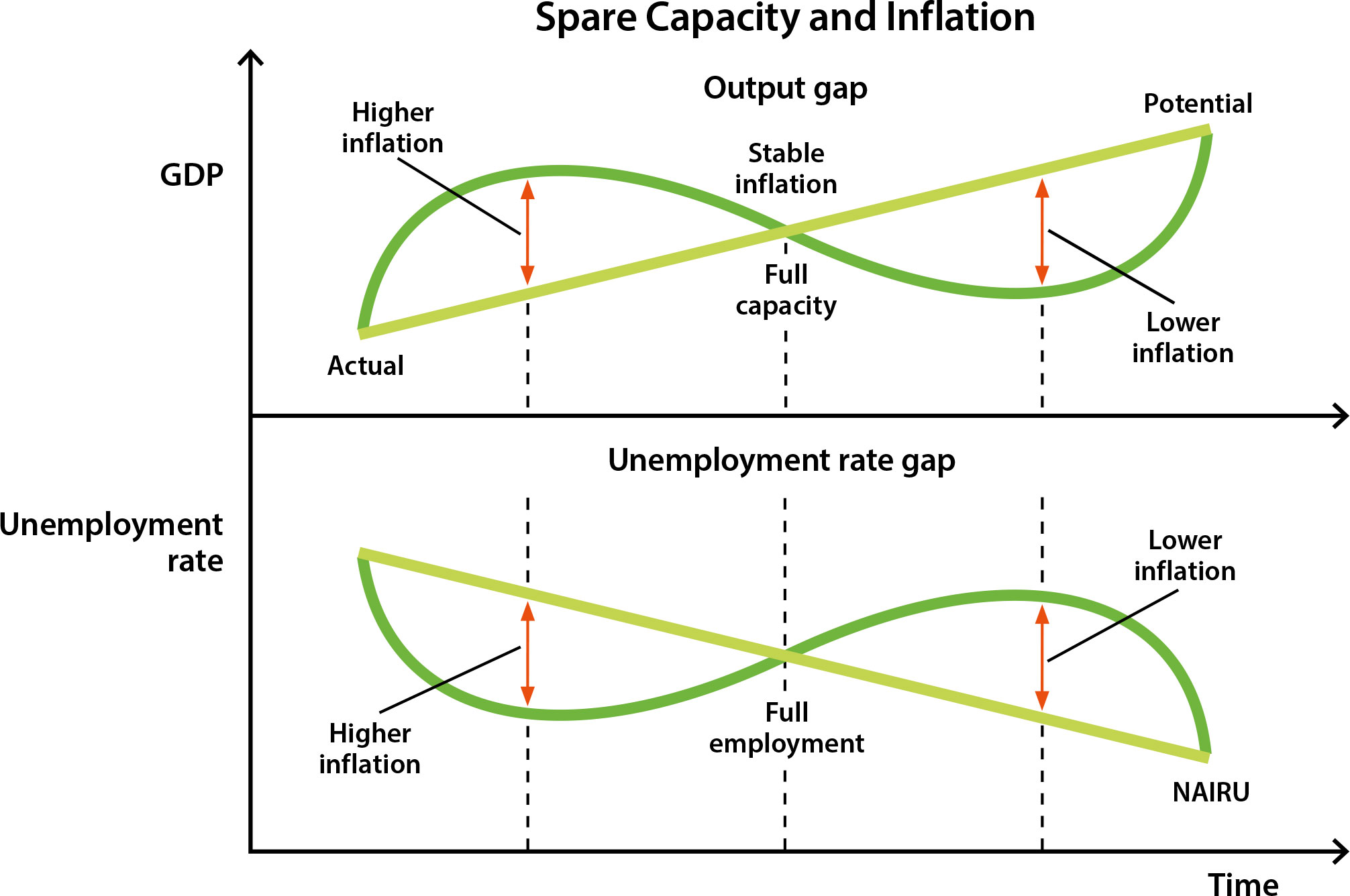

So how can we measure how far the economy is from its potential output (or full capacity) and what does this mean for inflation? While we can fairly accurately measure aggregate demand on a quarter to quarter basis using gross domestic product (GDP) data from the national accounts (see Explainer: Economic Growth), potential output is not directly observable − that is, we have to infer it from other evidence about the behaviour of the economy. For instance, just as there is a level of output where inflation is stable, there is also a level of the unemployment rate that is consistent with stable inflation. It is known as the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment or NAIRU for short (see Explainer: The Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU)). When unemployment is below the NAIRU, inflation will increase and when it is above the NAIRU inflation will decrease.

Causes of Inflation: demand-pull, cost-push and inflation expectations

Causes of inflation

The main causes of inflation can be grouped into three broad categories:

- demand-pull,

- cost-push, and

- inflation expectations.

As their names suggest, ‘demand-pull inflation’ is caused by developments on the demand side of the economy, while ‘cost-push inflation’ is caused by the effect of higher input costs on the supply side of the economy. Inflation can also result from ‘inflation expectations’ – that is, what households and businesses think will happen to prices in the future can influence actual prices in the future. These different causes of inflation are considered by the Reserve Bank when it analyses and forecasts inflation.[1]

Inflation

Inflation is an increase in the prices of goods and services.

The most well-known indicator of inflation is the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures the percentage change in the price of a basket of goods and services consumed by households (see Explainer: Inflation and its Measurement).

The CPI is the measure of inflation used by the Reserve Bank of Australia in its inflation target, where it aims to keep annual consumer price inflation between 2 and 3 per cent (see Explainer: Australia's Inflation Target).

Other measures of inflation are also analysed, but most measures of inflation move in similar ways over the longer term.

Causes of inflation

The main causes of inflation can be grouped into three broad categories:

- demand-pull,

- cost-push, and

- inflation expectations.

Tuesday, 28 May 2024

High capex companies are usually bad investments as they rarely produce enough free cash flow

Supermarket companies, in general have consistently spent more on capex than depreciation and produced very low free cash flow per share compared with EPS for many years.

For example: Sainsbury's

Sainsbury's has regularly spent more on capex than its depreciation expense for the period 2006 to 2015. At the same time, it has reported no meaningful growth in profits as measured by EPS.

Its capex to depreciation ratio for 2006-2015 ranged from 120% to 240%.

Despite all this investments (capex), EPS has not grown (In 2010 EPS was 30 p and in 2016 EPS was 22.5p.) and its FCFps has been negative for every one of these ten years,

Question to ponder

How much of the money spent on capex was to grow the business and how much was needed to maintain its existing assets and sales?

If most of this capex was actually needed for maintenance, then Sainsbury's depreciation expense may have been too low and its profits too high.

Take home point

Regardless of what the reason is for the high capex, these kind of companies are usually bad investments as they rarely produce enough free cash flow.

The above situation probably explains why Sainsbury's share price went nowhere over a 10-year period from 2005 and 2015 and why Sainsbury's had to cut its dividend payment to shareholders.

How depreciation of assets can distort profit figures

Depreciation is an expense that matches the cost of a fixed asset against the revenues it helps to produce. The cost of an asset is spread over its useful life.

The most common method of depreciating an asset is known as straight-line depreciation, where an equal amount is charged against revenue over the asset's useful life and is calculated as follows:

straight line depreciation = (cost - residual value) / estimated useful life

Depreciation is often seen as a proxy for maintenance or stay in business capex.

The problem with depreciation is that the management of a company can make it whatever value they want. The easiest way to do this is to say that assets will last longer than they will in reality.

Example

If an asset costs $10 million and will last for 10 years and be worth nothing after that time, the depreciation expensed against revenues for the next 10 years will be, $1 million per year.

($10 m - $ 0)/10 years = $1 million per year

In order to maintain the value of assets at $10 million, the company will have to spend $1 million on new assets each year (the amount it has depreciated by).

This is why depreciation is often seen as a proxy for maintenance or stay in business capex.

What if the $10 million asset only really lasts 5 years?

Depreciation should be $2 million per year instead of $1 million and profits should be $ 1 million lower.

If a company depreciates an asset by $1 million a year but actually spends $2 million to keep the asset up to date, then capex will be twice as much as depreciation but profits will be overstated by $1 million.

This will be picked up in the FCFps number but not the EPS.

Monday, 27 May 2024

Looking for possible investment candidates: Four simple rules when comparing FCFps with EPS

Summary

Expenses and depreciation reduce profits. Capex reduces FCF.

When expenses are not expensed against revenues but considered as capex, the company will report higher profit. Also, the depreciation charge reported by the company will be probably too low.

In a nutshell:

- the cash spent should be expensed against revenues and so it should reduce profits.

- unless it does, this, the depreciation charge reported by the company is probably too low and profits too high.

Four simple rules when comparing FCFps with EPS when looking for possible investment candidates:

1. Definite candidate: FCFps is 80% or more of EPS

2. Possible candidate: FCFps less than 80% of EPS and ROCE is increasing

3. Avoid: FCFps less than 80% of EPS but ROCE is falling

4. Avoid: FCFps is consistently negative.

If free cash flow per share is consistently a lot lower than EPS, this is a warning sign.

The 2 main reasons for FCF being lower than a company's EPS are:

1. Poor operating cash conversion

2. High levels of investment in new assets.

Poor operating cash conversion

This tends to occur when a company is growing quickly and sells a lot of its goods and services on credit.

The profits on these sales get booked in the income statement but there are no cash flows until the customer pays.

Companies may also build up stocks or inventories in anticipation of selling more. This is fine as long as the reason is genuine.

But building up stocks is also a good way for companies to shift overhead costs such as labour away from the income statement in order to boost profits. This can happen when companies include the overhead costs of producing stock in the balance sheet value. If the stock is unsold at the year-end that overhead cost has not been expensed through the income statement and can therefore boost profits.

Selling products on credit can be a sign of overtrading, or even fictitious sales. This sort of thing never turns out well for shareholders, so you need to watch out for this.

2. High level of investment in new assets

This is when capex is much higher than depreciation.

Depreciation reduces profits, but money spent on capex reduces free cash flow.

In this case, free cash flow per share will be a lot less than EPS.

- Capex that is consistently higher than depreciation with improvement in ROCE

It is not necessarily a problem for a company to spend heavily on capex, as long as the capex is earnings a decent ROCE.

[Example: Easyjet in 2015. Its FCF per share was less than its EPS due to capex being significantly more than depreciation. However, this is not a cause for worrying too much, as the company's ROCE had been increasing at the same time.]

- Capex that is consistently higher than depreciation with NO improvement in ROCE

However, capex that is consistently much higher than depreciation with no improvement in ROCE is rarely the hallmark of a great company.

It can be a sign of dodgy accounting as companies can and do shift expenses into capex to boost profit.

When FCF per share is a lot less than EPS it may also be a sign that a company is manipulating its profits to make them look bigger than they really are.

In these cases, capex is often much higher than depreciation but the company might be spending this cash just to maintain its existing assets, rather than using the expenditure to enhance it s income-producing assets.

- In a nutshell, the cash spent should be expensed against revenues and so it should reduce profits.

- Unless it does, this, the depreciation charge reported by the company is probably too low and profits too high.

Quality companies turn most of their profits into free cash flow on a regular basis

We can use free cash flow as a tool for checking the quality of a company's profits.

The stock market has been littered with companies that seemed to be very profitable but turned out to be anything but.

Investors can save themselves a lot of heartache and some painful losses by taking a few minutes to study how effectively a company converts profits into free cash flow.

One of the simplest and best ways to test the quality of a company's profits and whether you think they are believable or not is to compare a company's underlying or normalised earnings with its free cash flow.

The free cash flow will show you how much surplus cash the company has left over to pay shareholders. It can often be very different from EPS, even though it is supposed to tell you the same thing. For most years, you want to see the free cash flow has been close to earnings.

Calculating free cash flow

Example: Company Z ($ m)

Net cash flow from operations 69.0

Capex -6.8

FCF to the firm (FCFF) 62.7

Minority or preference dividend paid 0.0

Interest paid -0.3

Interest received 0.0

FCF for shareholders (FCF) 62.4

Weighted average number of shares in issue 504.6m

FCF per share 12.37 sen

Underlying EPS 11.9 sen

Quality companies turn most of their profits into free cash flow on a regular basis

Checking the safety of dividend payments

Dividends are an important part of total returns from owning a share.

Dividends are a cash payment and therefore the company needs to have enough cash flow to make these payments.

Compare the FCF with its dividends

By comparing the free cash flow with its dividends, you can see whether a company has sufficient cash to pay dividends.

Net cash from operation - CAPEX = Free Cash Flow

You want to see the free cash flow being the bigger number more often than not.

When dividend is the larger number compared to the free cash flow, this may occur when a company is putting cash to good use (capex). When dividend is the larger number is fine on occasional years. Prolonged periods of insufficient free cash flow will often lead to dividends being cut or scrapped eventually.

When analysing a company, it is often a good idea to compare free cash flow with the dividends over a period of ten years.

FCF dividend cover

A quick way to check whether cash flow is sufficient to pay dividends is by using the free cash flow dividend cover ratio. This is calculated as follows:

Free Cash Flow dividend cover = Free cash flow / dividends.

When free cash flow exceeds the dividends by a big margin, it can be a sign that the company may be capable of paying a much bigger dividend in the future.

Sunday, 26 May 2024

When free cash flow may not be what it seems

Free cash flow comes with a few caveats one need to be aware of.

Besides calculating a company's free cash flow, one need to study its cash flow statement closely to really find out what is going on.

Example: Company Property X - no free cash flow but paying dividends

Operating profits 830m

Other (operating) (648m)

Operating cash flow 182m

Tax paid -

Net cash from operations 182m

Capex (441m)

Free cash flow (259m)

Equity dividends paid (139m)

This is a property company. Making money from selling properties (assets) is a normal part of its day-to-day activities. It makes sense to consider the sales of assets a part of the free cash flow.

Free cash flow (259m)

Add back asset sales 1,358m

ADJUSTED FCF 1,099m

Equity dividends paid (139m)

This company is more than able to pay its dividends to its equity owners.

Always need to study the cash flow statements to understand what is really going on.

Example: Company Serial-Acquirer Y - lots of free cash flow but regularly buying companies

Occasionally, one comes across companies that seem to be producing lots of free cash flow when in reality they are not.

If you study the investing section of the cash flow statement more closely, large cash outflows might not be found in the capex section but can be found somewhere else, such as acquisitions.

Operating profits 46.3m

D&A 13.1m

Profits on disposals (1.6m)

Change in working capital `1.3m

Other (operating) 1.3m

Operating cash flow 57.9m

Tax paid (14.4m)

Net cash from operations 43.5m

Capex (6.9m)

Free cash flow 36.6m

Equity dividends paid (9.7m)

This is a company that keeps spending a lot of money on acquisitions regularly and yearly.

Acquisition (18m)

ADJUSTED FCF 18.6m

For this company, the cash spend on acquisitions should probably be used to calculate free cash flow, in order to give a fair picture. When this is done, its free cash flow is significantly reduced.

This company may be too reliant on buying other companies to produce the cash flow needed to pay its dividend. Before looking at this company as a potential investments, one would certainly want to investigate this further.

Tuesday, 14 May 2024

CHECKLIST ON HOW TO VALUE SHARES

BIGGEST RISK: PAYING TOO MUCH

The biggest risk you face to be a successful investor in shares is paying too much.

It is important to remember that no matter how good a company is, its shares are not a buy at any price.

Paying the right price is just as important as finding a high-quality and safe company.

Overpaying for a share makes your investment less safe and exposes you to the risk of losing money.

USUALLY HAVE TO PAY UP FOR QUALITY

Be careful not to be too mean with the price you are prepared to pay for a share.

Obviously, you want to buy a share as cheaply as possible, but bear in mind that you usually have to pay up for quality.

Waiting to buy quality shares for very cheap prices may mean that you end up missing out on some very good investments.

Some shares can take years to become cheap and many never do.

CHECKLIST ON HOW TO VALUE SHARES

When valuing shares, you can use the following checklist to remind of the process to follow:

1. Value companies using an estimate of their cash profits.

2. Work out the cash yield a company is offering at the current share price. Is it high enough?

3. Calculate a company's earnings power value (EPV) to work out how much of a company's share price is explained by its current profits and how much is dependent on future profits growth. Do not buy shares where more than half the current share price is dependent on future profits growth.

4. Work out the maximum price you will pay for a share. Try and buy shares for less than this value. At least a discount of 15% or more.

5. The interest rate use to calculate the maximum price should be at least 3% more than the rate of inflation.

6. You must be very confident in continued future profits growth to pay a price at or beyond the valuations estimated here.

7. The higher the price you pay for profits/turnover/ growth, the more risk you are taking with your investment. If profits stop growing, then paying an expensive price for a share can lead to substantial losses.

Can quality be more important than price?

The importance of growth

If you are going to buy and own expensive shares, you must be very confident that high rates of growth can continue for a long time into the future. Since no one can predict the future accurately, you need to protect yourself by not paying too high a price for shares.

Knowing how to value shares and understanding the crucial relationship between cash profits and interest rates are important. Know how much of a company's current share price is based on its current profits and how much is related to future profits growth.

Though profits growth is important in valuing shares, you should also know how to not pay too much for it.

High share prices can unravel very quickly when profits stop growing.

Companies which investors like tend to command very high valuations because they are growing turnover and profits rapidly, or are expected to do so Their shares will have very high multiples of profits and cash flows and very low yield attached to them.

This can persist for a long time but the dangers for investors of owning expensive or highly-rated shares can be significant when profits stop growing.

Investors in these shares may often lose a large amount of their investment and learned a brutal lesson of the high risks of owning expensive or highly-rated shares. This experience has been repeated countless times in the past and will surely happen many times again int he future.

Using owner earnings to value shares: Setting a maximum price method

Setting a maximum price and buying price for Company X shares

Current cash profit per share 11.6 sen

Divide by interest rate [inflation +3%] 4.4%

Maximum price (cash profit / interest rate) $2.636

Current price $3.20

Ideal price at 15% discount $2.24

Cash yield at ideal price (cash profit/ideal price) 5.18%

ANALYSIS:

This approach is saying that Company X shares are currently too expensive to buy.

The most (maximum price) you should pay is $2.63 per share, compared with a current share price of $3.20.

If you want even more of a buffer (margin of safety) compared with the maximum price - a good rule of thumb is 15% - you will only want to pay $2.24.

Additional notes:

You might be waiting a long time for a share to reach your target price and it might never do so.

However, it is far better to wait or even risk missing out on the few shares that are too expensive than to risk paying too much and lose money.

When to sell?

This kind of analysis can also give you some guidance of when to sell a share.

If a share that you own reaches a maximum price, it doesn't mean that you should automatically sell it. Shares can and do go beyond and below their fair valuations.

In the above example, Company X, one would not sell at $2.63 but if the share price exceeded this (maximum price) by 25% ($3.29), you might sell and then look for something cheaper to buy.

Using owner earnings to value shares: Earnings Power Value (EPV)

EPV gives an estimated value of a share if its current cash profits stay the same forever.

Calculation:

1 Normalised or underlying trading profits or EBIT

2. Add back D&A

3. Minus Capex

4. Derive Cash Profit or Owner earning

5. Tax this cash profit by the company's tax rate.

6. Divide by a required interest rate to get an estimate of total company or enterprise value.

7. Minus debt, pension fund deficit, preferred equity and minority interest to get a value of equity. Add any surplus cash.

8. Divide by number of shares in issue to get an estimate of EPV per share.

Compare the estimate EPV per share with the current share price.

Existing share price >>> EPV

A large chunk of the current share price is based on the expectation of future profit growth.

Share price <<< EPV

EPV can be a great way to spot very cheap shares.

When you come across a share like this, you need to spend time considering whether its current profits can stay the same, grow or whether they are likely to fall. If profits are likely to fall, it might be best to move on and start looking at other shares.

To minimise the risk of overpaying for a company's shares, you should try to buy when its current profits (its EPV) can explain as much of the current share price as possible.

As a rough rule of thumb, even if profits and cash flows have been growing rapidly, do not buy a share where more than half its share price is reliant on future profits growth.

Example

Company X 2015 ($m)

EBIT 73.7

D&A 6.6

Stay in business capex -8.9

Cash trading profit 71.3

Tax@20% -14.3

After tax cash profits (A) 57.0

Interest rate (B) 8%

EPV = A/B 713

Adjustments

Net debt/net cash 40.4

Preference equity 0

Minority interest 0

Pension fund deficit 0

Equity value 753.4

Shares in issue (m) 497.55

EPV per share ($) 1.514

Current share price ($) $3.20

EPV as % of current share price 47.3%

Future growth as % of current share price 52.7%

INTEREST RATES

Some rough guidelines of the interest rates you might want to use when valuing different companies:

Large and less risky companies: 7% to 9%

Smaller and more risky (lots of debts or volatile profits): 10% to 12%

Very small and very risky: 15% or more.

Using owner earnings to value shares: Cash yield or Interest rate method

This approach is very simple.

Take the owner earnings or the cash profit per share and divide it by the current share price to get a cash interest rate (or yield)

Cash interest rate = cash profit per share / share price

Rational

The whole point of owning shares is to get a higher return on your money so that you can grow the value of your savings.

If you are going to get only a small cash interest rate on your shares at the current share price, it could be a sign that the shares are overvalued.

What a low interest rate is telling you is that cash profits are going to have to grow a lot in the future to allow you to get a decent return from owning the shares.

Investing is all about interest rates.

To make money you should aim to try and get the highest rate of interest on your investments as you can without taking lots of unnecessary risks.

Only you can decide what rate of interest is high enough.

EXAMPLE of using cash yield or interest rate method to value share

Let's say that you want to get a 10% cash flow return on buying shares in Company X where the cash profit per share is 11.6 sen. At its present share price of $3.20, you are currently getting a cash yield or interest rate of 3.6%. You need to work out what annual rate of growth over what length of time would be needed to get to 10%. (Best way is to set up a spreadsheet and play around with some growth scenarios.)

Assuming a 10% annual cash profit growth:

In year 3, the cash profit per share is 15.4 sen, giving a cash yield of 4.8%.

In year 10, the cash profit per share is 30.1 sen, giving a cash yield of 9.4%.

Scenarios analysis

This kind of exercise can teach a great deal about what a $3.20 share price for Company X says for the company's future cash profits. A lot of future growth is already baked into the share price. It takes a reasonably long time with a reasonably high growth rate to get a reasonable cash yield on buying the shares at $3.20.

Profits are going to have to grow faster than 10% per year to get to an acceptable cash yield in a shorter time. Even if you wanted a 7% return, you would have to wait seven years at a 10% growth rate. That is a long time to wait.

What if growth is a lot lower than 10% or even if profits fall? The chances are that Company X's share price would fall, which means you could end up losing money.

What does a low cash yield means?

It means that you are paying for growth in advance of it happening.

It will take years of high growth in cash profits to get a reasonable return on your $3.20 buying price.

This is one of the most risky things that you can face as an investor.

You can protect yourself by insisting on a higher starting interest rate when buying shares in the first place.

Look for an interest rate of at least 5% and even then, you have to be very confident that growth would be high for many years in the future.

How to set your buying price for a 5% or 8% initial cash yield?

Take the cash profit per share and divide it by 5% or 0.05. For Company X with a cash yield of 11.6 sen, this gives:

11.6 sen/ 0.05 = $2.32

Even more cautious, and wanted a starting yield of 8%, then your buying price would be

11.6 sen/ 0.08 = $1.45

These results of $2.32 and $1.45 make Company X share looks well overpriced at $3.20