Compound interest, or growth, is one of the, if not the most, powerful and impactful forces in nature.

Simply, we misapply the term "compound growth" to things that do not actually grow in compound fashion.

Let's first establish what "compound growth" even means.

The fact is, very few objects, organisms or organizations can sustain truly compounding growth over any extended period.

From an observer's or investor's perspective, it's quite easy to fool yourself into thinking compound, exponential growth is much more common than it really is. And it's understandable given how often the term is thrown around. Firms in fleeting phases of fast growth can visually demonstrate their breakneck pace with the ubiquitous, infamous "hockey stick" chart.

As an entrepreneur or operator, you too can fall prey to your own fictions - convincing yourself you've "cracked the code" when you've only really cracked the piggy bank. Irrational exuberance eventually turns concave, finally ending in a plateau of linearity.

Through some examples, I hope to demonstrate that compound growth 1) implies constant growth 2) is exceedingly rare and 3) is incredibly important to building a large, valuable business.

But before we get to business, let's talk about - bacteria.

In bacteria populations, growth is fixed. Subject to the resource constraints of the environment they inhabit, bacteria grow at a constant rate indefinitely.

A simple example to illustrate the point:

Let's say we have some bacteria that reproduce on a fixed time schedule, one doubling per minute to keep the numbers simple.

We start with a single bacteria cell. After one minute, we'll have two bacteria. With time, the population grows as such:

Now we ask the question, how fast does our bacteria population grow (in percentage terms)?

The number of bacteria cells one minute from now is:

nt+1=2nt

Which implies the minute-over-minute growth rate is:

nt+1nt−1=2ntnt−1=2−1=1

or 100%.

This is an example of perfectly compounding growth, also referred to as exponential or geometric growth.

Put simply, how fast the bacteria grow is entirely independent of population size. In other words, growth and scale are perfectly uncorrelated.

Importantly, most things do not work this way.

Layering on

Let's look at another example - constructing a brick wall.

Assume a bricklayer can lay 10 bricks per hour. The brick count will proceed as follows

The brick count grows by 10 bricks per hour.

Going through the same growth rate calculations from above:

The number of bricks 1 hour from now will be:

nt+1=nt+10

Which implies hour-over-hour growth is:

nt+1nt−1=nt+10−ntnt=10nt

Notice that the growth rate depends on how many bricks we've already laid. This is linear or arithmetic growth. Because the number of bricks laid each hour is static through time, growth (in percentage terms) necessarily slows down. Scale is in the denominator. Therefore, growth and scale are negatively correlated: more scale -> less growth.

Sure, initially we are growing the brick count quite fast - 100% in fact. But by the time we reach 30 bricks, our forward-looking growth rate has fallen to 33%. At 100 bricks, we'll only be growing 10% - which is a far cry from our halcyon days of tech reporters and venture capitalists gawking at our growing (tech enabled) bricklaying operation.

Two flavors of growth

The key difference between the bricks and the bacteria is that one has scale invariant growth (SIG) and the other... doesn't.

OK OK, friends who reviewed this before publishing said that was a big word/phrase to suddenly drop. So let's take a step back and examine this phenomenon visually before moving forward.

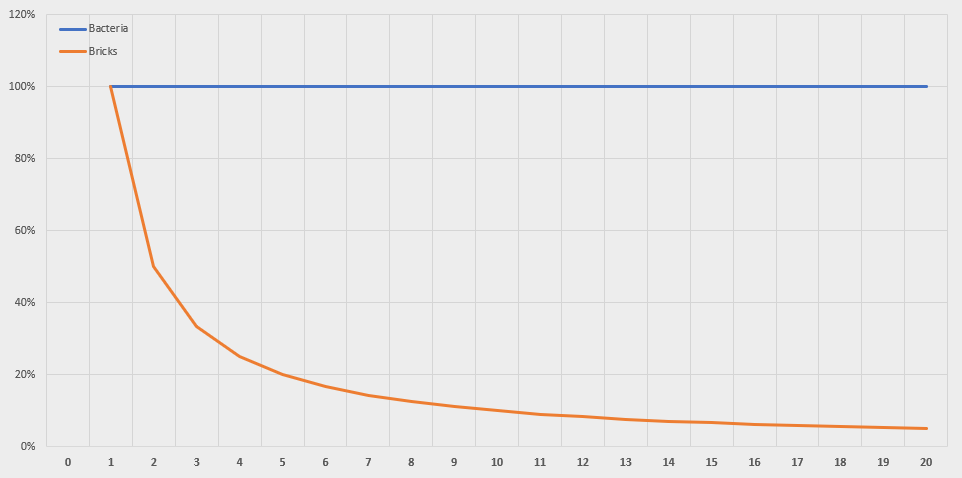

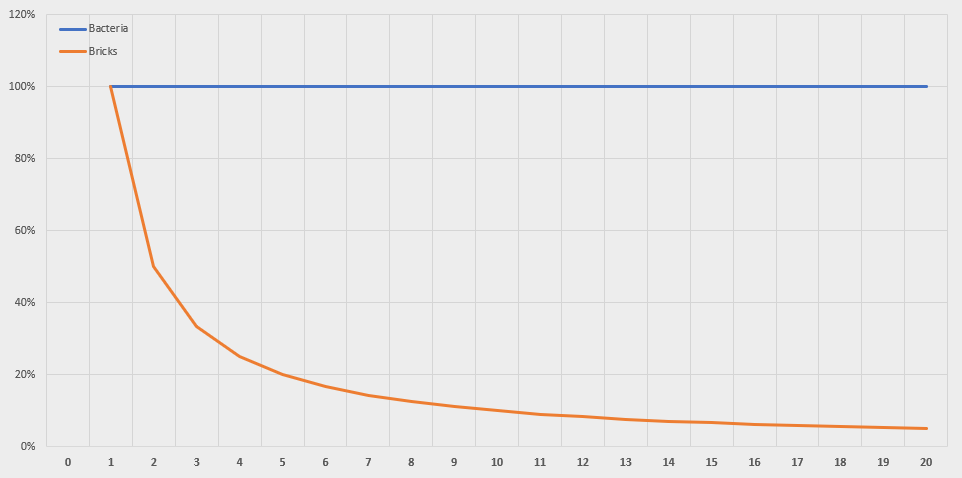

A great way to do this is plot the growth rate of the bacteria and bricks over time:

The bacteria grow at a constant rate over time. For the bricklayer, growth simply... collapses.

I've plotted this chart hundreds of times over the years, and for most startups the growth plot looks eerily similar to the bricks here.

Growth is not the natural order; growth cannot be taken for granted. As we get larger, we get slower.

I mentioned correlation earlier. The correlation between growth and scale in the case of the bacteria is 0 - perfectly uncorrelated.

For the brick count, the correlation is -0.7, a very strong negative correlation.

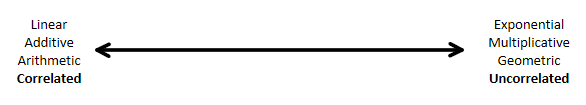

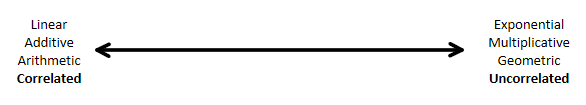

We've now established two ends of a spectrum we can use to characterize various forms of growth.

On one side, we have linear/additive/arithmetic/correlated growth, and on the other we have exponential/multiplicative/geometric/uncorrelated growth.

The question now is, where do various things fall along this spectrum? Said another way, how accurate is it to say that "XYZ" grows in compounding fashion?

Let's walk through some more examples.

Debt

Compound growth is often used in reference to compound interest earned on a financial instrument of some sort.

Anyone who has ever suffered through mounting credit card debt knows this quite well. Debt grows like bacteria - it multiplies without end at a rate that depends entirely on the interest rate and not at all on the current balance.

1%, 5%, 10% - whatever the interest rate, unless paid off, debt continues to grow without end. If only paid off partially, the remaining balance will continue to grow.

Not a bad business model if you ask me.

World GDP Per Capita

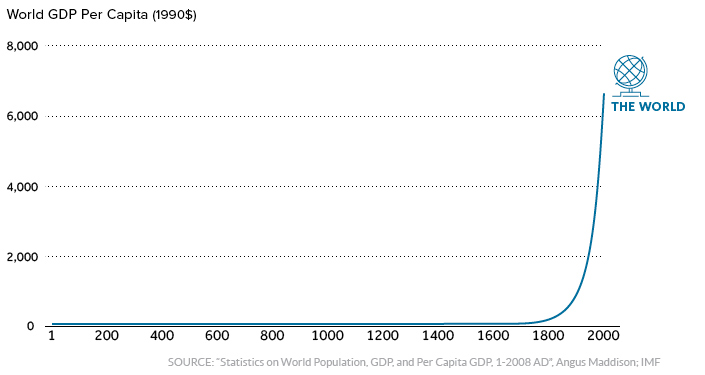

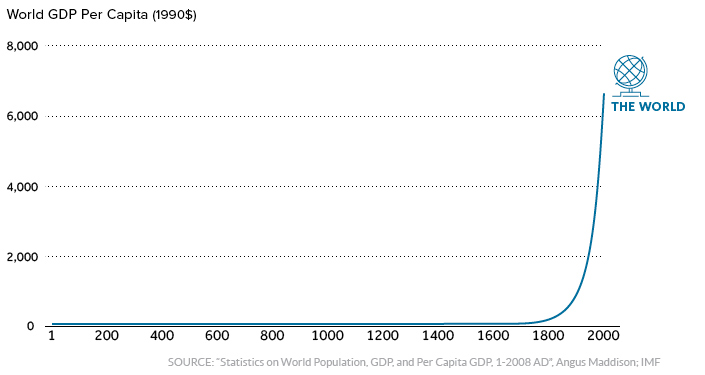

Growth is not the natural state of affairs. For most of human history there was no meaningful economic growth or improvement in livings standards for the average person. Until recently, Life was nasty, brutish, short and... static:

Unless growth is literally contractual, as in the case of debt and interest, we can't take it for granted, as history plainly shows.

And it's not simply a question of the scale of the axis. If you zoomed into that long straight line, you wouldn't see a hockey stick growth pattern. Living standards actually did not improve meaningfully over time for the vast majority of human existence on this planet.

A few years of bad weather, major epidemics like the Black Death (the bacteria strike again), social upheaval - these events drastically impacted the day-to-day well-being and lives of our ancestors, often erasing decades of progress.

Even today, many parts of the world experience major swings in their rates of growth, especially within the developing world. Regions and countries can end up in severe economic doldrums, leading to entire lost generations.

Many stops and starts, fits and spurts.

However, before we get too depressed, let's look at a best case scenario.

U.S. GDP

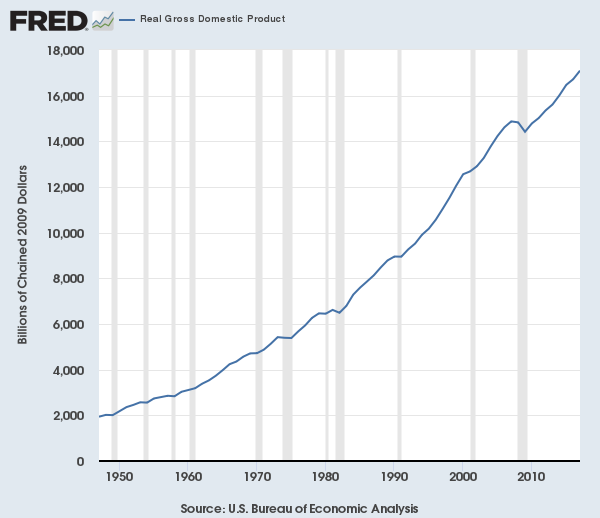

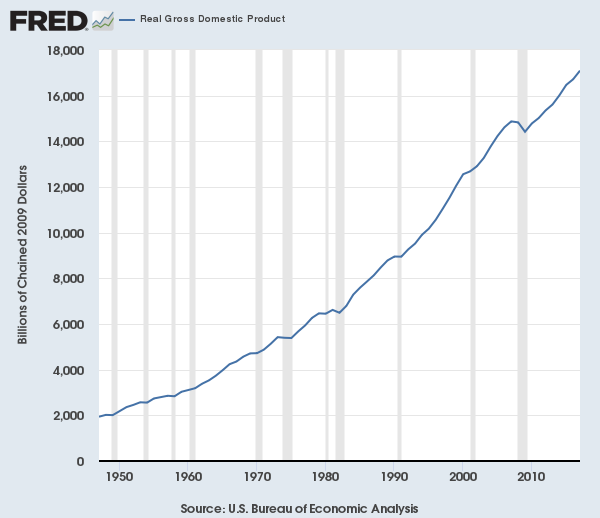

The good ol' US of A ('s real GDP):

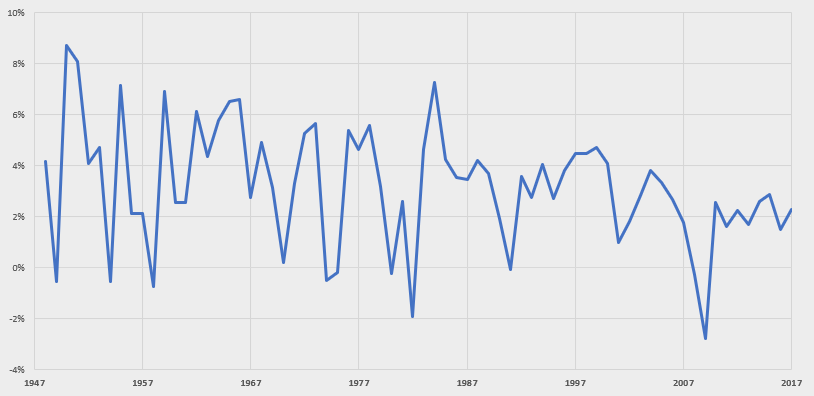

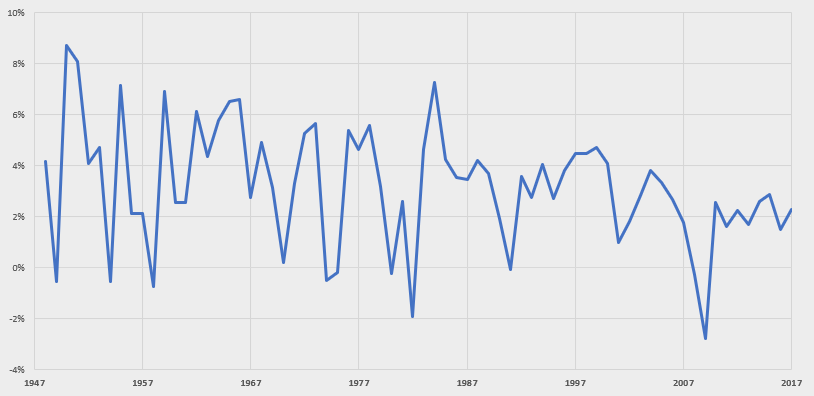

Looks pretty good huh? Let's look at the growth plot:

Ugh, this is pretty noisy. It's difficult to tell if growth is changing in significant ways year-to-year or if it is generally variation around a certain value.

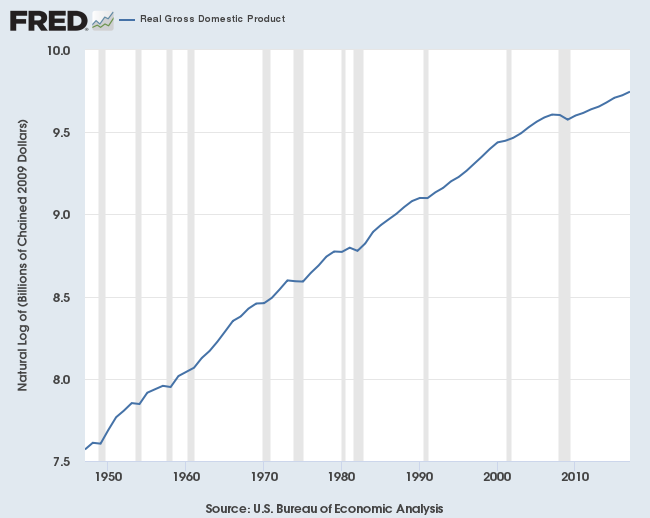

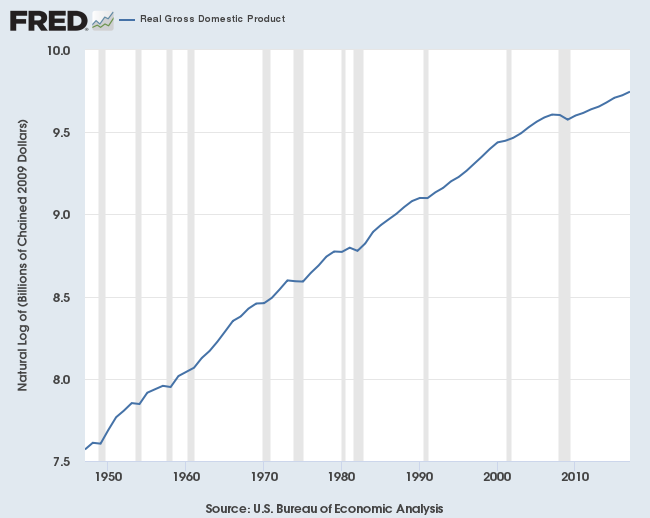

This view hides some interesting detail. One neat math trick - taking the natural log rescales a metric such that, when graphed, linearity implies constant growth.

Do this, and the real GDP chart becomes:

Over this period, we can make a few interesting observations:

- Log real GDP is impressively linear - one could fit a linear line to the above data fairly well, implying reasonably constant growth

- That said, it is not perfectly linear, and therefore not perfectly compounding, per our earlier definition

- We can see multiple distinct inflection points where growth changed, in connection with recessions (1970, 2008)

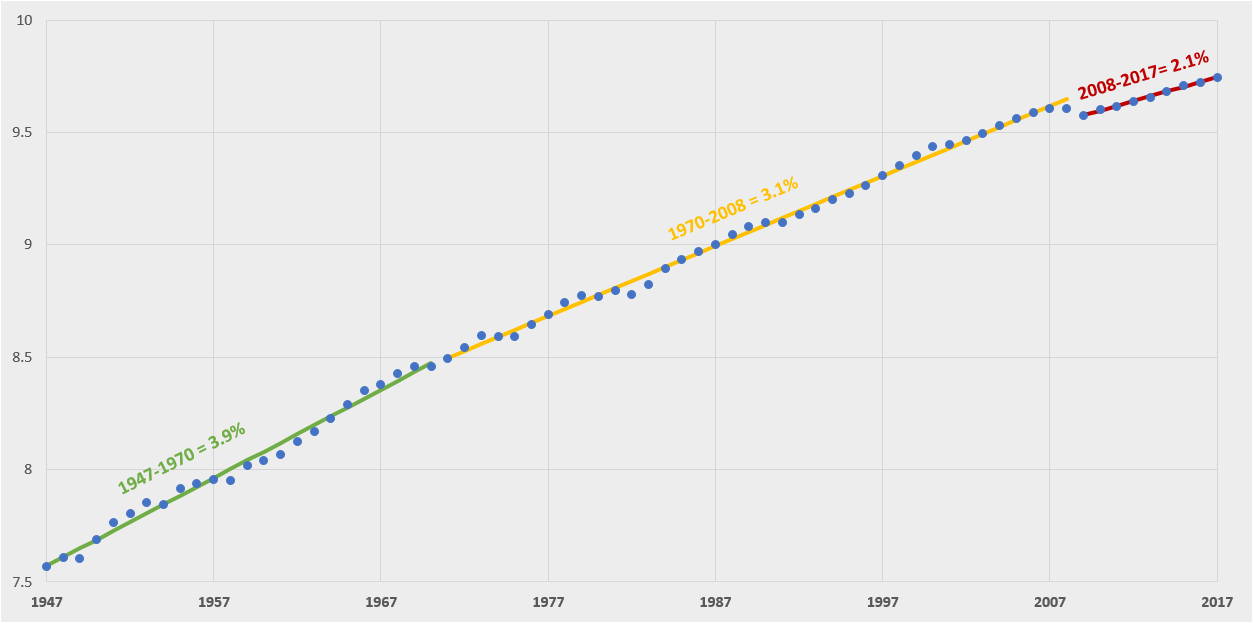

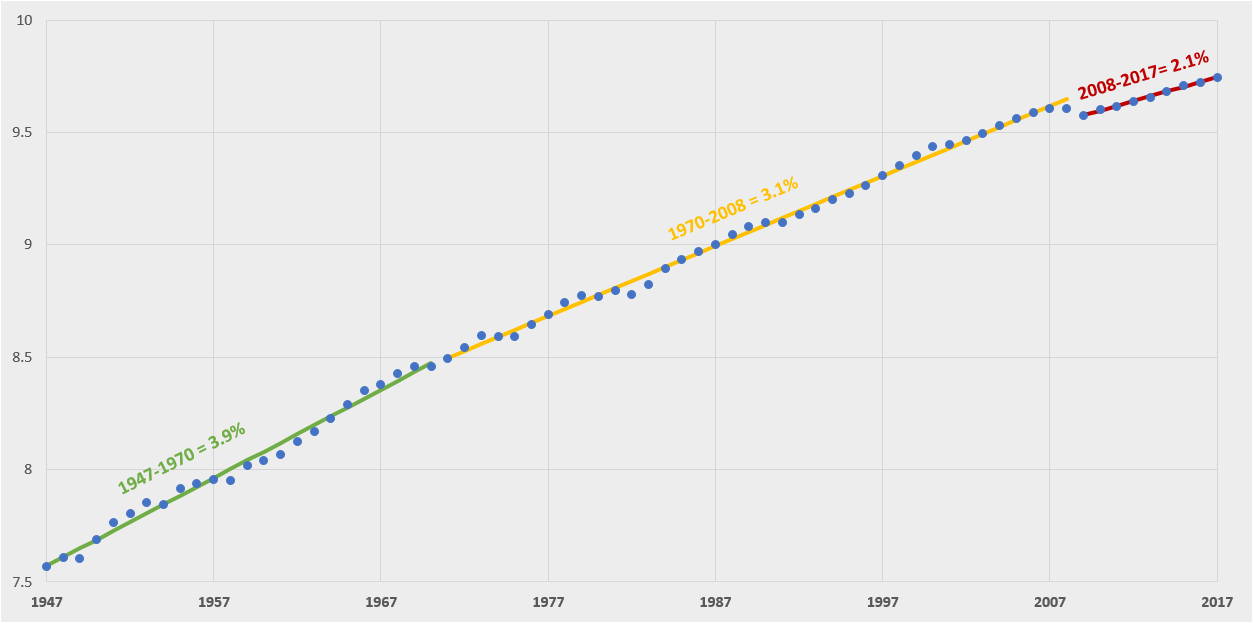

Taking advantage of these kinks in the curve, let's estimate the growth during each period through piecewise linear regression (i.e. the "line of best fit" for each period):

Annual real growth goes from 3.9% in the 1947-1970 period, to 3.1% in the 1970-2008 period, to 2.1% in the 2008-2017 period.

The economists yelling and screaming that we are on permanently lower trajectory after the most recent recession may have a point.

So not exactly constant growth, but still impressive given the real economy grew 8x+ over this period. Growth has roughly halved over a 70-year period.

In terms of the connection between growth and scale, the correlation here is -0.3, which certainly indicates a relationship, but not a strong one.

We can therefore conclude that U.S. GDP grows in reasonably compound fashion.

Revenue

Most businesses see their revenue growth rate tick down over time. This is even more true for companies that are growing quickly today.

On the other hand, some exceptional businesses have managed to drive truly compound growth over long periods.

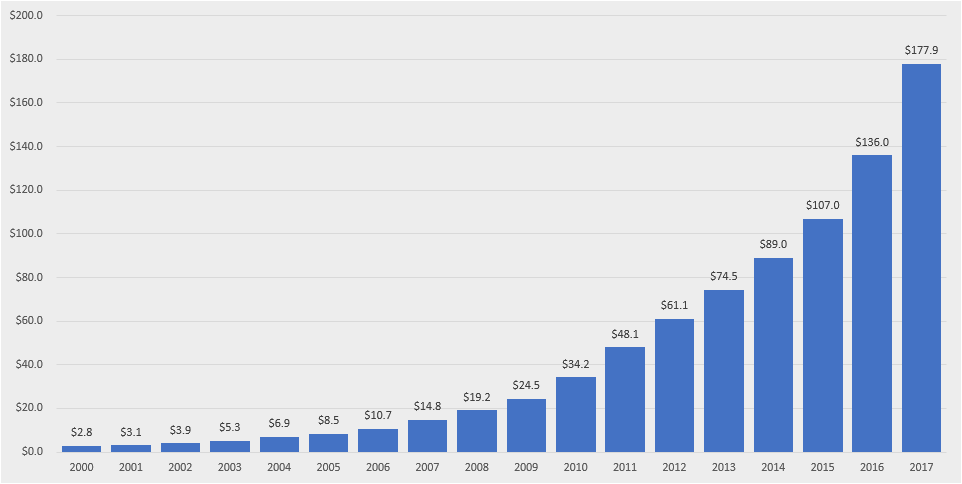

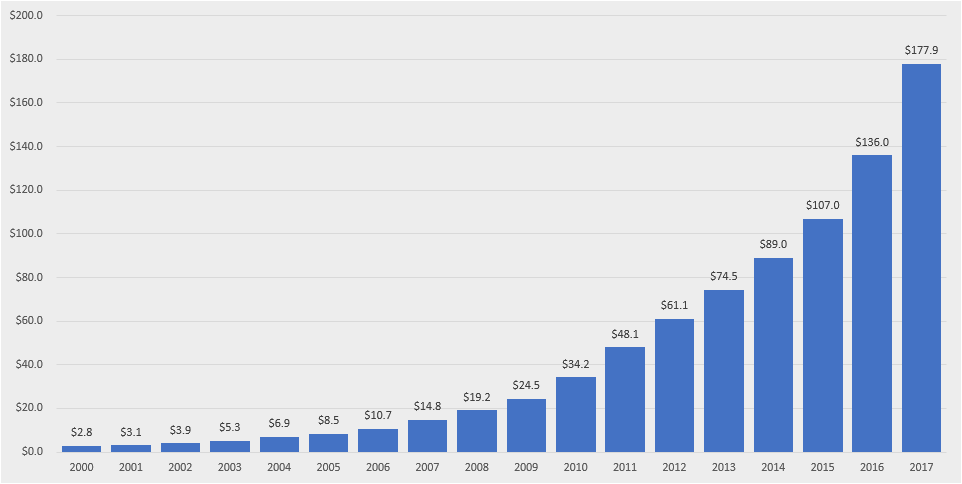

Take Amazon for example, which has exhibited incredible revenue growth over time ($B):

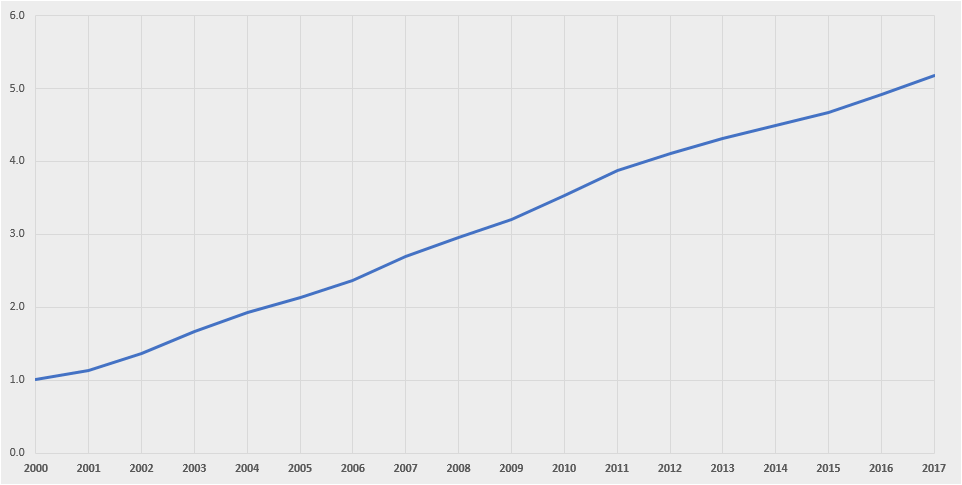

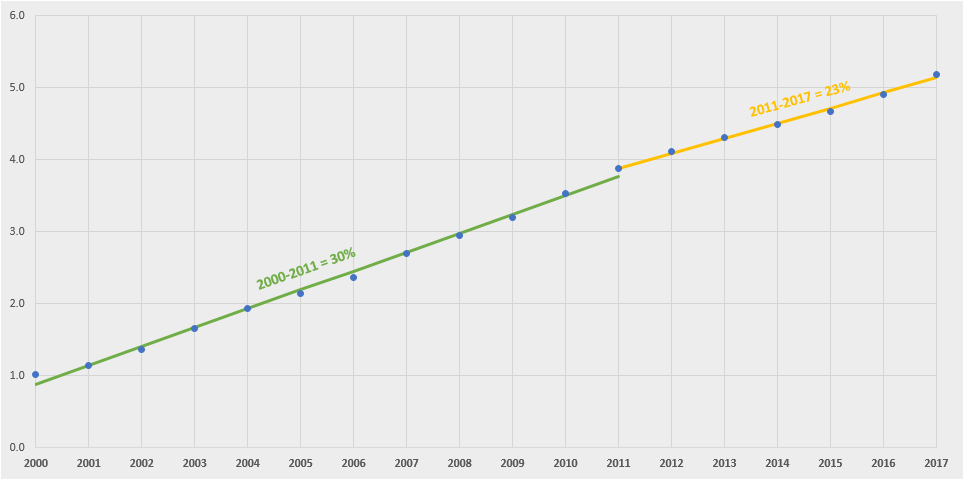

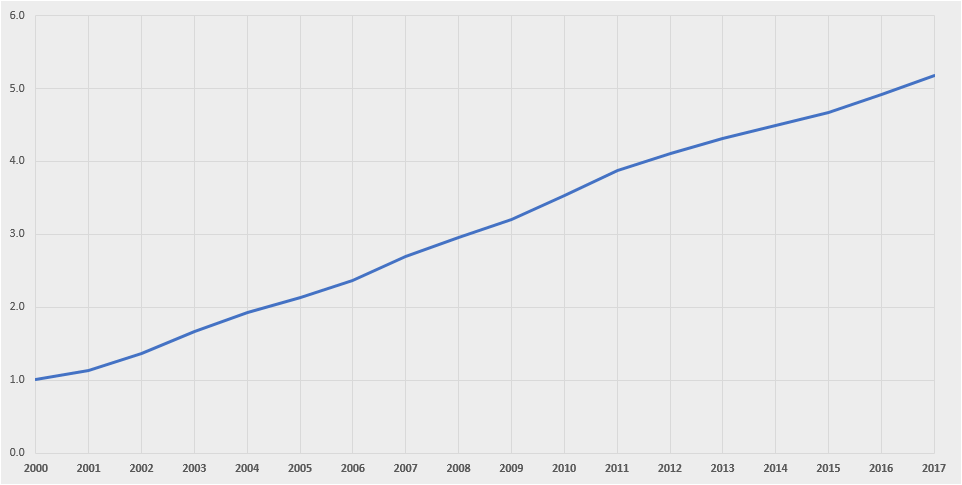

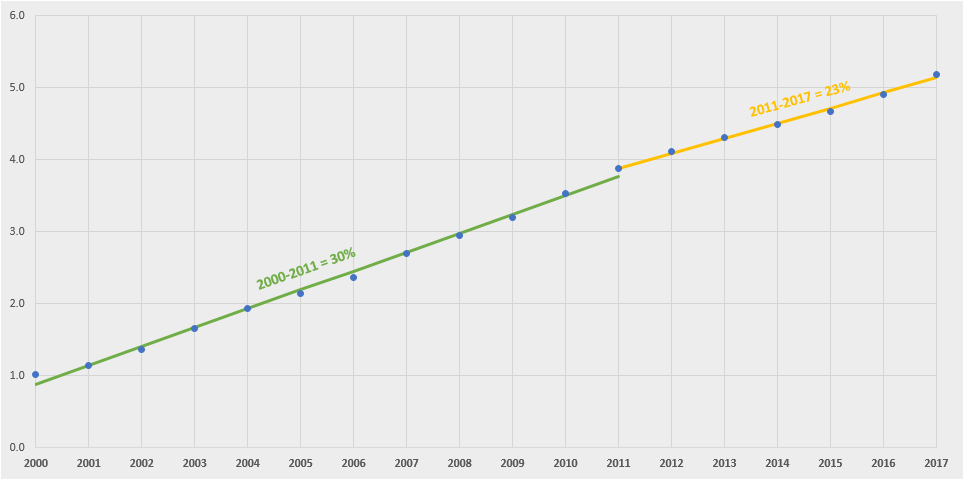

This is an impressive chart in its own right. But I am actually more impressed by the log-transformed chart, which is nearly a straight line:

Amazon has grown at a nearly constant rate over almost two decades, despite increasing scale by 64x over the period.

At best, one could identify a slight kink in growth in 2011. Replicating the piecewise analysis, we can see that Amazon grew ~30% year-over-year from 2000 to 2011 and ~23% year-over-year from 2011 to 2017.

Amazon's growth-scale correlation? -0.1!

It's hard to put into words how impressive that single number is. Worth reiterating: most things do not work this way.

Amazon is an exceptional business that has evidently identified a way to grow at a nearly constant rate over many years. A combination of tapping into the long-run secular growth of e-commerce and deft expansion into seemingly orthogonal spaces (for example, via Amazon Web Services) that in fact leverage the core infrastructure the company's built up over time has enabled it to grow in bacteria-like fashion.

Growth functions: Are you adding or multiplying?

Every growing business needs an honest answer to this question: Is your business growing through multiplication, like the Amazonian bacteria, or addition, like the brick wall?

Businesses that simply "add" must necessarily slow down, by the simple math we outlined earlier. Scale begins to work against you, making it harder and harder to maintain a rapid growth pace. Eventually, you will, figuratively, hit a wall.

An example of an additive growth function is paid customer acquisition through a channel like Google Adwords.

Spending $100 on Adwords is going to generate some number of users. Spending another $100 is probably going to generate a similar number of users, and so on.

There's no "magic" here. This is "buying growth" in the most direct manner.

If anything, customer acquisition through paid channels that you do not control (and Adwords is the epitome of this) tends to get less efficient over time as you saturate keywords etc.

Like a bricklayer at the end of a long day, businesses reliant on this form of growth tend to run out of gas sooner or later.

Sure, you can attempt to stack bricks at a faster and faster rate, raising venture capital when you can no longer self-fund the endeavour, building the wall ever higher...

But this too will pass. Eventually, some proportion of those users must stick around and continue to buy from you without meaningful additional spend on your part, otherwise you'll find yourself on the proverbial "acquisition treadmill", unable to jump off without significant disruption to the business.

A number of companies in the subscription e-commerce "send me a box with a psuedo-random assortment of goods" space fall squarely into this category. Users churn at high rates, requiring more and more fuel to be poured on the paid acquisition fire to keep the train going.

On the other hand, businesses that "multiply" can grow indefinitely. Their "growth functions" are inherently multiplicative. Users beget more users. Revenue begets more revenue.

The classic exponential, multiplicative growth function is the viral word-of-mouth (WOM) or referral program.

PayPal built a viral engine in its early days, giving users money for each additional friend they referred to the service:

Dropbox replicated this, giving out additional space for signing up friends: